The Full Eight Unks

David Simmonds

A friend and musical collaborator was putting on a concert in Ottawa a few weeks ago. He asked me to participate by singing a nonsense song I had written a few years ago called the “Chipmunk Strut.” Fastidious readers of this column will recall the song earned me precisely $36.10 in royalties; I don’t want it to the lead item of my epitaph.

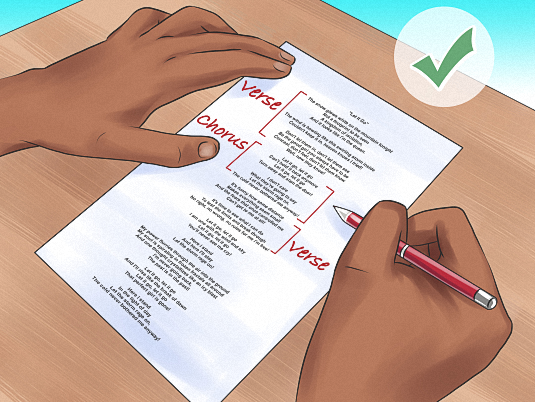

• Re-learning a long I wrote.

The ties of friendship prompted me to accept the invitation. With a couple of weeks to go before the big event and not having played the “Chipmunk Strut” for a long time, I set out to re-learning it. Surely, this can’t be hard, I told myself, especially since it was my own creation.

The conceit of the song is to create various rhymes around the “unk” in “chip-munk.” I sing about a “chip-munk,” that’s living in a “‘chip-bunk, and plays his banjo with a “chip-plunk.” This goes on through eight different “unks.”

To re-learn the song, I began pacing around my room singing the song time after time, assuming that repetition would do the trick of re-entering it in my memory. Yet, every time I told myself that next time through I would perform it flawlessly, I hesitated or stumbled over some line. This wasn’t going to be as easy as I thought.

The Waring House kitchen party, hosted by the Frere Brothers, took place just three days before the big concert. It offered an open mike opportunity for me to try out my full eight-unk routine. After having repetitively rendered the song in the safety of my car, all the way to the pub, I felt confident as I stepped up to the mike that I could ace this performance.

I began all right. Yet, as my brain was finishing the oration of the first couple of unks, I asked it to roll out the next couple to have on the tip of my tongue. My brain refused to assist; it was a total blank. I’d never foundered at this point in the song before. I was stranded; thus, I improvised by slurring my words and making it appear that it was the audience’s fault if they didn’t catch my meaning. I left the stage a much-humbled man.

Fortunately, I had a forgiving or indifferent Waring House audience. I still had three days to overcome whatever obstacles prevented me from giving the work the performance it deserved. A sceptic might argue I had just given the song the performance it deserved.

Needing more than constant repetition, I turned analytical and decided to memorize a prompt word to remind me of the third and fourth rhymes and to pause for a break and collect my wits at two points in the song. This seemed to do the trick. The performance at the show went off, barely, without a hitch.

• Tips for remembering song lyrics.

I was wised up enough by the Waring House episode that when I got back from Ottawa I searched for advice from the commons of the internet, keying in “10 tips to help remember song lyrics.” Some of the advice I couldn’t use. Constant immersion and repetition I had tried.

Apparently, Frank Sinatra wrote lyrics out by hand as a way of learning them, but I had already done that. I had also already adopted the cue word technique. I could not use the internal “unk” rhymes as clues, because they were everywhere in the song.

I befriend the song. I sympathize with its point of view. Well, okay, but I’m not sure how that directly helps me remember unks five and six.

There were two practical tips on the internet. One, when you are learning a song with multiple verses, try memorizing the first line of each verse. Then learn the first and second, then the first, second and third and so on. This is stacking. Two, treat the lyric as a story told in a logical and orderly way: what should come next probably does.

This struck a nerve. My friend had also asked me to perform his musical setting of Edward Lear’s poem “The Owl and the Pussycat.” I found it much easier to commit to memory than the Chipmunk Strut.

The poem tells a decidedly wacky story that unfolds, relatively speaking, in that logical and orderly way, whereas the “Chipmunk Strut” is all wordplay, without a storyline. To test this proposition, I chose a story song, “Me and Bobby McGee.” I found I could indeed recall the words just by continuously asking myself “Okay; what happens next?”

• Decisions, decisions, decisions.

I face a choice. Do I continue writing and performing songs, such as the “Chipmunk Strut,” with its big $36.10 payday, and run a risk that forgetfulness will overtake me at any moment and wreck a performance. Do I start writing and performing songs with stories that I can remember? Another option may be occurring to you at this point, but I would ask that you keep it to yourself.

Some readers seem intent on nullifying the authority of David Simmonds. The critics are so intense; Simmonds is cast as more scoundrel than scamp. He is, in fact, a Canadian writer of much wit and wisdom. Simmonds writes strong prose, not infrequently laced with savage humour. He dissects, in a cheeky way, what some think sacrosanct. His wit refuses to allow the absurdities of life to move along, nicely, without comment. What Simmonds writes frightens some readers. He doesn't court the ineffectual. Those he scares off are the same ones that will not understand his writing. Satire is not for sissies. The wit of David Simmonds skewers societal vanities, the self-important and their follies as well as the madness of tyrants. He never targets the outcasts or the marginalised; when he goes for a jugular, its blood is blue. David Simmonds, by nurture, is a lawyer. By nature, he is a perceptive writer, with a gimlet eye, a superb folk singer, lyricist and composer. He believes quirkiness is universal; this is his focus and the base of his creativity. "If my humour hurts," says Simmonds,"it's after the stiletto comes out." He's an urban satirist on par with Pete Hamill and Mike Barnacle; the late Jimmy Breslin and Mike Rokyo and, increasingly, Dorothy Parker. He writes from and often about the village of Wellington, Ontario. Simmonds also writes for the Wellington "Times," in Wellington, Ontario.

- Charitable Space Invaders

- Thoughts from Away

- Obits Blitz

- A Bit of a Smell

- A Fait Not Complete

- The Golden Pancake

- Make Taxes Fun

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- A Mature Product?

- All Dumplinged Up

- Fried Rumours

- Sjef Frenken

- All Things Considered

- Jack, Rick and I

- Dog Heaven

- Jennifer Flaten

- Howa Garden Grows

- Crisis! Alert!

- Fictional Fairy Tale

- M Alan Roberts

- Real Men

- American Nightmare

- Please Eat Me

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Downloaders

- Valentine's Day 2016

- Red Velvet Cupcakes

- Streeter Click

- Howard Lapides Top 40

- Gabe Abelson

- A Brief Review

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- The Road Forward

- The Path Forward

- Our Last Christmas

- Jane Doe

- US Election 2016

- The Jazz Age

- Guitar Woods

- M Adam Roberts

- Christmas Angels

- No Greater Love

- Last Stand

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Future

- Monkey Business

- Harmony