Obits Blitz

David Simmonds

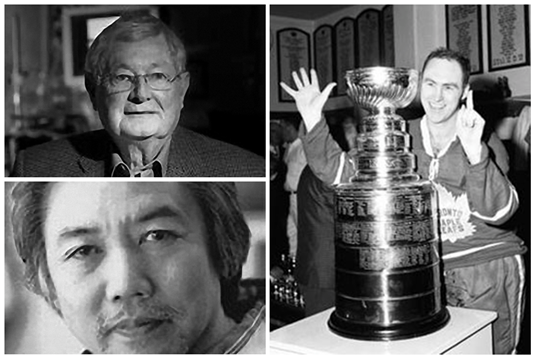

Upper left, Dr Wilbur Keon; lower left, Wayson Choy; right, Red Kelly.

Time was when I would eagerly await the arrival of the morning newspaper to read about the political shenanigans of the day. Then I aged; I became wiser and turned to the comics first. As middle age settled over me, the siren of baseball box scores lured me to the sports page. Then the Sudoku and Kenken puzzles had top priority.

► Obits are often complete stories.

Now, I dive into the obituaries, the obits, right way. I have been asking myself just why; trying to look beyond the old joke that when I don’t see my name in there, I know I’m still alive. I think the main reason, I dive into the obits, is simply that obits tell a story, a complete life story, with a beginning, a middle and an end.

I’ve saved a few obits from the last week or so and the variety of human experience they embrace is amazing. I’ve noted four of them, three Order of Canada recipients and one that was definitely not Order of Canada material.

First up is Leonard Patrick “Red” Kelly, late of the Detroit Red Wings, the Toronto Maple Leafs and the House of Commons. Kelly passed away at the age of 91. He played on eight Stanley Cup winning teams in the Original Six Teams era, four with each of the Wings and Leafs.

Perhaps more remarkably, he was a four-time winner of the Lady Byng trophy for “sportsmanship and gentlemanly conduct combined with a high standard of playing ability.” He grew up on a tobacco farm in Simcoe, Ontario; he signed as many as four hundred autographs a week. Ringo Starr does not sign autographs. Kelly once said, “[Mine’s] a short name; I sympathize with Mahovlich.”

Then there was Dr Wilbert Keon, who left us at age 83. He was the youngest of eleven children in a family from Sheenboro, Quebec. He performed over ten thousand heart surgeries, was the founder of the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, installed the first artificial heart in Canada and was described by Ottawa mayor Jim Watson as, “‘the closest thing to a saint Ottawa has.” That proposition bent, slightly, when a soliciting sting caught Keon. Even though eleven thousands people wrote in support of Keon and the Heart Institute declined to accept his resignation, he had to attend a school for johns. He died of heart failure.

► Inspiring young Asian and gay writers.

Next up was Wayson Choy, who died at age 80. He published an award-winning novel The Jade Peony, in 1995; it’s a story based on his childhood in the Chinatown area of Vancouver. Later he published a memoir, Paper Shadows: a Chinese childhood. His gentle and evocative writing style was a vivid introduction to many Canadians to the Chinese experience in in Canada. He was an inspiration and mentor to many young Asian and gay writers.

The odd man out, in the group, is William Krehm; he passed at 105 years of age. Krehm was the last living Canadian volunteer in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939. The International Brigades, including some 1,600 Canadians, went to Spain to fight for the Republican government against the Nationalist Rebellion of Francisco Franco, who ultimately won, with the support of Germany and Italy, and held control of the country until the 1970s. While in Spain, Krehm crossed paths with George Orwell, who wrote Homage to Catalonia about his Spanish experiences.

As many in the International Brigades, Krehm was a communist, but one that picked the wrong side in his affiliations. He supported Leon Trotsky, a rival to the eventual successor, Lenin, Joseph Stalin. Stalinists worked their way into the Spanish Republican government and purged the anti-Stalinist militia that Krehm joined. Krehm went to jail along with other members of the militia. Some died in prison; he was fortunate enough for Spain to expel him.

Trying his luck as a foreign correspondent in Latin America, Krehm interviewed Trotsky, in Mexico City, in 1940. The next day, an agent of Stalin murdered Trotsky. Krehm is reputed to have stood guard over Trotsky’s body at the funeral home.

On his return to Canada, Krehm could not count on regular employment owing to his communist beliefs and the constant presence of the RCMP. Thus, he became a successful property developer in Toronto. He also worked as an occasional music critic for the Globe and Mail and wrote books on economics.

There you have it, four extraordinary lives, having in common only how they ended at roughly the same time and they inspired us, in one way or another. Most of us live ordinary lives, happy if we make it to a respectable three score years and ten, content that we loved and, in return, found love with at least other person.

► My light shines on.

Our ordinary lives can inspire as well, a subject I’ll return to in a future column. Next on my agenda, however, now that I’ve checked today’s obits, are the Sudoku and Kenken puzzles. I may be old, but my late middle aged light still shines, brightly.

Some readers seem intent on nullifying the authority of David Simmonds. The critics are so intense; Simmonds is cast as more scoundrel than scamp. He is, in fact, a Canadian writer of much wit and wisdom. Simmonds writes strong prose, not infrequently laced with savage humour. He dissects, in a cheeky way, what some think sacrosanct. His wit refuses to allow the absurdities of life to move along, nicely, without comment. What Simmonds writes frightens some readers. He doesn't court the ineffectual. Those he scares off are the same ones that will not understand his writing. Satire is not for sissies. The wit of David Simmonds skewers societal vanities, the self-important and their follies as well as the madness of tyrants. He never targets the outcasts or the marginalised; when he goes for a jugular, its blood is blue. David Simmonds, by nurture, is a lawyer. By nature, he is a perceptive writer, with a gimlet eye, a superb folk singer, lyricist and composer. He believes quirkiness is universal; this is his focus and the base of his creativity. "If my humour hurts," says Simmonds,"it's after the stiletto comes out." He's an urban satirist on par with Pete Hamill and Mike Barnacle; the late Jimmy Breslin and Mike Rokyo and, increasingly, Dorothy Parker. He writes from and often about the village of Wellington, Ontario. Simmonds also writes for the Wellington "Times," in Wellington, Ontario.

- Obits Blitz

- Blue Hats

- Oriental Philosophies

- Smothers Brothers Syndrome

- Disappointments

- Vellingtunne

- An Average of Nine

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Thick and Quick

- Crows and Cards

- Musical Memory Moments

- Sjef Frenken

- Blackitude

- A Reminiscence

- Charity Begins at Home

- Jennifer Flaten

- The Agogny of the Artist

- Fish Business

- Kitchen Help

- M Alan Roberts

- Green: same old lies

- What the USA Needs

- A Loveless Life

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Chasing Shadows

- Being Polite

- More Teenage Hormones

- Bob Stark

- Fuddle-duddle

- RIP Stompin Tom

- NHL Final 2013

- JR Hafer

- Popcorn Sutton

- Rosko

- Why and Wherefore

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Unwelcome News First?

- Little Memoires

- Back to the Past

- M Adam Roberts

- Lazy Bones

- Christmas Angels

- I Owe You

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Unicorn

- The Future

- There is a Light