Patsy Cline

Jennifer Flaten

Invisible Immortality

"A lot of people, in Ginny Hensley's staid, upright home town, regarded her as hillbilly trash," writes Paul Duggan, in the "Washington Post" for 30 April 2005.

"She was poor, coming of age in a Shenandoah Valley town, of Winchester, Virginia, after World War Two. Into the 1950s, she sang in any beer dive. She worked regional radio and the Moose Lodge circuit, boasting she'd get to Nashville."

Her betters gossiped. "What a hussy," they said. "Young Virginia going around, with her ruby lipstick and short pants, crawling under the covers with this one and that one."

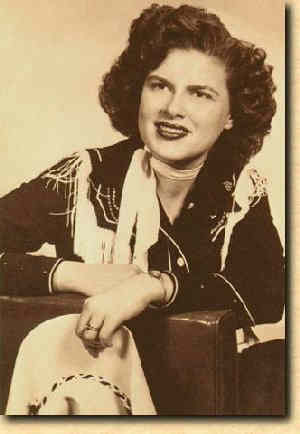

Virginia Hensley about 1949

Unlike celebrities, who died young, such as Jim Morrison or Elvis Presley, the grave of Patsy Cline is no shrine. There's no graffiti, no eternal flame, no lines of sobbing fans, only prayer beads and plastic flowers. Cline lays below a simple stone, bearing her family name, Dick.

Her grave is in Shenandoah Memorial Park. "I peered closer," writes Pamela Gerhardt, in the "Washington Post" for 14 October 1998. "I found her birth name, Virginia Patterson Hensley. Below that, in parentheses and smaller type, almost an afterthought, is Patsy Cline."

A recently renovated Hudley high school includes a theatre that bears her name; cline dropped out of school at age 15. Winchester, Virginia, thought enough of its hussy to name a street or two for her, the gossipers forgotten. Her childhood home is for tourists, marked with a heritage plaque.

Cline childhood home at 608 S. Kent St., Winchester, Virginia

Margaret Jones, in "Patsy: the life and times of Patsy Cline," tells a revealing story. In May 1957, the 25-year-old Cline rode on top of the back seat of an Oldsmobile convertible, in the Apple Blossom Festival parade. She returned, triumphant, to Winchester, Virginia, after winning on 'Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts,' for singing, "Walkin' After Midnight."

A worn homecoming-parade photograph, May 1957

The brief life of Patsy Cline is gripping. A genuine hero, her music most American, Cline goes unnoticed. She rose from rags to riches, against all odds, which is usually enough to earn a halo.

Perhaps it's gender. Janis Joplin, better known, in death, than Cline, doesn't have the standing of Jimi Hendrix or Jim Morrison. Few recall "Mama" Cass Elliot or Jayne Mansfield; the memory of Marilyn Monroe fades, blending with "Princess Di."

Perhaps the lack of mystery about her death is a cause of the low profile. On Tuesday 5 March 1963, a plane, carrying her home to Camden, Tennessee, crashed. The exact moment of death is known, 6:20 pm; her watch jammed when the plane slammed into the ground.

Buddy Holly, whose memory survives, with the aura of a medieval martyr, died in a plane crash, too, 49 months, almost to the day, before Cline. Holly and Cline were flying in single-prop planes to make up time. You'd think such minutiae would set the hearts of "Access Hollywood" producers pounding, but doesn't.

Photographs from late 1940s and early 1950s

The story of Patsy Cline is worth telling. Her voice, with its smokey, bluesy twang, sends shivers up and down the spine. Her songs tell adult stories every generation and each gender understands. Her talent and career reset the bar for women, and men.

"Grand Ole Opry," about 1939, live on WSM-AM

The "Grand Ole Opry" is the home of Country Music. WSM-AM, in Nashville, started airing the "Opry" on Monday, 5 October 1925. At first, the "Opry" had a cast of imaginary yokels; by the 1950s, it was the crown jewel of Country Music and radio.

"Opry" performances were by invitation only. Singers or bands worked for years or decades to earn an invitation to the "Opry." Only those on the Country Music A-list had a chance at an invitation; the "Opry" was an exclusive club.

Although she appears on the "Opry," since 1956, Cline became a full time member in 1961. She's the only person to ask to join the "Opry," without a turn down. Cline became the most popular "Opry" singer, until her death, in 1963.

Patsy Cline was Country Music Royalty. "Crazy," written by Willie Nelson and purchased, by Cline for $250, made her a lasting star. The legacy of "Crazy," the most played song on juke boxes, since its release, put Cline on the A-list, with Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley, among others.

Other hit songs, such as "Walkin' after Midnight," "I Fall to Pieces" and "She's Got You," made Cline a crossover star. These songs were top ten hits on Country as well as on Pop and Rock charts. In the 1950s, Country Music was hokum for bumpkins, not sophisticated city folk: Cline changed that image.

Presley quickly left Country Music for Pop fame. The insatiable need for music, from the mushrooming local radio industry, gave kowtowing to Pop and Rock its appeal. Cline held true, selling genuine, unaltered Country Music to pop and rock audiences.

Born Virginia Patterson Hensley, on Thursday, 8 September 1932, in Winchester, Virginia, no hints of immortality were obvious. Her father, Sam, was a blacksmith who abandoned the family in 1947. Her mother, Hilda, was a tailor who raised three children in a poor, if happy, home, on the wrong side the tracks.

Cline was the oldest of the three Hensley children. In 1932, her mother was 16 years old. As do many children, Patsy often said she would grow up to be famous.

When father, Sam, abandoned the family, Patsy left school to help support her siblings, Samuel and Sylvia. During the day, she worked menial jobs. At night, she chased her passion, singing.

Cline had perfect pitch. From age 8, she played piano, but didn't take singing seriously until her early teens. Her smokey voice, prone to sultry slurs, Cline said, was the result of a throat infection during childhood. Her confident and ebullient stage presence was both a façade and a sign of determination: she would be a star.

Shyness wasn't her long suit. Cline entered talent contests, winning most, and never missed a chance to sing for an audience. At 14 years of age, taking her destiny by the scruff of the neck, she asked Jimmy McCoy, of WINC-AM, if he'd allow her to sing on his show.

McCoy hosted a local talent show. Cline made her radio debut on WINC-AM, in 1952. Later, McCoy said he couldn't resist her charm and Cline sang, on the show, every Saturday night for many months.

She sang with "Bill Peer and His Melody Boys," starting in 1952. Peer convinced Cline a variation of her middle name, Patterson, was more stage friendly than was Virginia. Singer Virginia Hensley became superstar Patsy Cline.

In 1953, Hensley met building contractor, Gerald Cline. They married on 30 September. Cline wanted his wife to focus on the household and not her career, but she wanted to sing. Patsy kept his name after they divorced, in 1957.

Peer took Cline seriously. He helped her become a regular on "Town and Country," a television show in Washington, DC; Jimmy Dean was also a regular. Peer renegotiated her recording contract, with Four Star Records; now she picked songs she recorded.

Newly renamed, Patsy Cline found success. She appeared on radio and television more often, her records aired on local stations and her live shows drew larger audiences. When she asked to appear on the 'Grand Ole Opry," it was in the interest of the "Opry" to agree.

Cline debuted on Saturday, 7 January 1956. She wasn't yet a full member. For five years, she was a regular guest on the "Opry."

Now, her contract, with Four Star Records, held her back. Cline recorded fifty-one singles, for the label, only two of her own songs. At Four Star, she developed a presence in Country Music and likely opened the door to the "Opry," but her career needed more development.

Her "Opry" appearance, carried by the ABC Television Network led to more television. In January and March, of 1956, Cline appeared on another ABC-TV show, "Ozark Jubilee." Charlie Dick, the lynchpin in the career of Patsy Cline, watched all her television appearances, closely.

In 1957, Cline met Dick. He knew she sang a good song, had a style. He came to see her, to listen for a while.

Dick caught her attention, too, as she sang. He was handsome, with a reputation as a man who enjoyed women. Cline liked what she saw, but wondered about his intense interest in her singing.

He had a true appreciation of Cline and her talent. When Dick became involved with Cline and her career, she began to soar. Peer prepared Cline, well, for success; Charles Dick launched her.

Cline took an instant liking to Charles Dick. They quickly became openly chummy. Their rapport was controversial, in the serious 1950s.

Once her divorce from Gerald Cline finalized, Cline and Dick married. "He's the love of my life," she said, referring to Charles Dick. Their marriage was stormy, but endured until her death.

Despite marital turmoil and a fast-tracking career, Cline and Dick had a daughter, Julie, in 1958, and a son, Randy, in 1960. In 1958, the family moved to Nashville. Nearness to A-list artists, recording studios and producers would help her career.

A few months before the move to Nashville, there was a case of mother knows best. Mom, Hilda Hensley, talked Cline into trying out for the television show, "Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts." She easily won a spot on the show for Sunday, 21 January 1957.

She auditioned using "Walkin' After Midnight," a pop song she felt pretentious; she was a Country Music singer, not Patti Page. "Walkin'" combined the transparency, of Country Music and the tonality of Pop, with the grittiness of R&B, says Geoffrey Himes, of the "Washington Post." It was the perfect antidote, for Nashville and Country Music, after the Elvis Presley shockwave.

For this show, the producers demanded she wear a cocktail dress instead of a cowpoke outfit, hand sewn by her mother. Her performance on Godfrey was a success. She appeared, regularly, on his show, for the next two months.

During one Godfrey show, the producers substituted "Walkin'" for "A Poor Man's Roses," at the last minute. The audience response was overwhelming. Four Star Records released "Walkin'," as a single, on 11 February 1957.

on "Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scout", April 1957.

The record reached number twelve on the "Billboard Country Music Chart" and the "Billboard Hot 100." A pop song, written by Don Hecht and Alan Block, Cline reluctantly recorded it. Thus, it was available for quick release after the Godfrey show.

"Walkin'" became a major crossover hit for Cline. Country, Pop and Rock music stations played "Walkin'." It peaked at number two, on Country Music chart and number twelve on the "Billboard Hot 100," a pop chart.

A crossover, from Country to Pop, was rare at the time and meant new opportunities. During the late 1950s, Presley, Brenda Lee and the Everly Brothers earned such hits. Presley and Lee opted for the more profitable Pop genre. The Everly Brothers segued into early Rock 'n' Roll. Only Cline tried to remain true to Country.

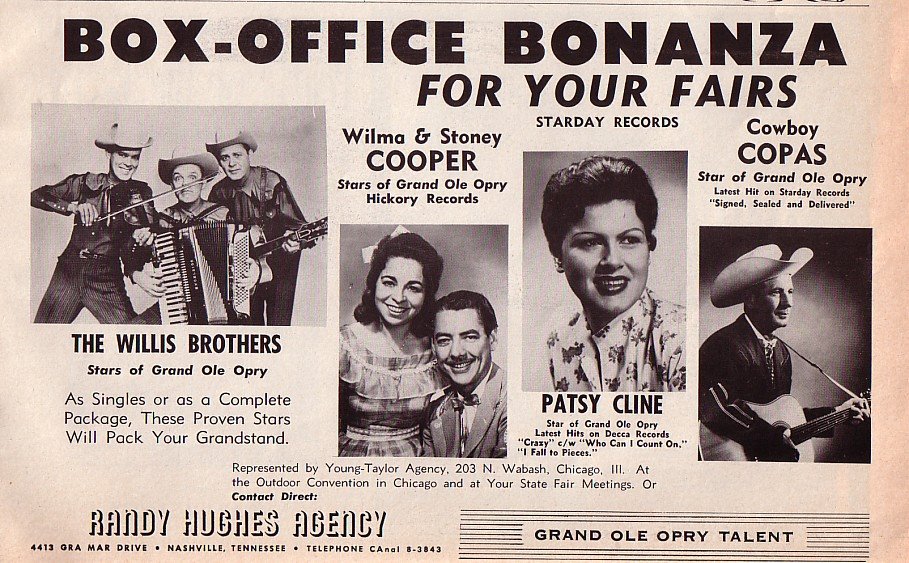

In 1960, perhaps to stabilize her marriage, Cline found a new manager, Randy Hughes. On 9 January 1960, she signed a new recording deal, with Decca-Nashville, too. At Decca, Owen Bradley, who worked with Brenda Lee and Loretta Lynn, produced Cline.

Decca Team: Owen Bradley, Randy Hughes, Cline,

Justin Tubb, Hank Cochran

Bradley, who thought her voice fluid and full, helped Cline refine her vocal work; he also liked her reckless vocal confidence, which Presley also showed. They played down the country twang, stressing an instantly recognizable, smokey, silken, sultry and soulful bluesy tone. Bradley urged Cline to record Pop as well as Country songs, an idea she didn't like, saying she was a Country Music singer.

In the end, Cline agreed to record Pop songs. It was strictly a career move. Audiences loved her pop songs and she sold millions of crossover records.

In 1961, Cline had mixed luck. "I Fall to Pieces," written by Hank Cochran and Harlan Howard, was a crossover hit. It was number one, on Country Music Charts, and peaked at number six on the "Billboard Hot 100." The combination of "Walkin'" and "I Fall to Pieces" made Patsy Cline a household name.

She joined the cast of the "Grand Ole Opry," as a full member. This confirmed her place on the A-list of Country Music entertainers. A childhood musing came true: Virginia Patterson Hensley was famous, if as Patsy Cline.

On 14 June 1961, Cline had a near-fatal car accident, a head-on collision, and spent a month in hospital. A visible scar remained on her forehead, after the accident, which caused her much concern. Yet, she went on with her life, resuming a tour, using crutches to mount the stage.

To trade on the crossover success of "I Fall to Pieces" and make up for her month in hospital, Decca suggested Cline record "Crazy." She disliked the song, written by Willie Nelson and his idiosyncratic style. After trying to mimic Nelson, Cline recorded "Crazy," as she wanted, and it became her signature song.

"Crazy" was a major hit. It peaked high, on two "Billboard" charts: number two, on the "Country Chart" and number nine, on the "Hot 100." Although not the "Crazy" Willie Nelson imagined, audiences remember the Cline version best.

Unexpected fallout came from "Crazy." Until this point, women were usually opening acts, often with no billing. After "Crazy," Cline headlined shows and tours, always getting top billing.

In 1962, Cline co-headlined a show, at the Hollywood Bowl, with Johnny Cash. She was the first Country Music performer to play Carnegie Hall, in New York City; the first women, in Las Vegas, to headline a show. She headlined her own tours, too.

At the height of her popularity, Cline earned $1,000 a show. This was an unheard-of amount, at the time, let alone for a woman. For her next to last concert, she earned $3000; her last show was a charity event.

Early in 1962, songwriter Hank Cochran called Cline. "I just wrote your next number one hit," he said. "Come over and play it for us, now," she said. Cochran played "She's Got You" for Cline and her friend, Dottie West.

Cline loved the lyric. Immediately, she called her manager and producer: she wanted to record the song as soon as possible. "She's Got You" released on 30 January 1962, topping the country chart and peaking at fourteen on the "Hot 100."

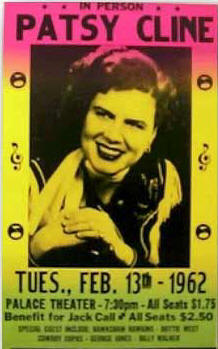

A series of ordinary recordings followed "She's Got You," her last hit. In February 1963, thirty-year-old Cline recorded her final album, "Faded Love." After a benefit show (see poster, above), in Kansas City, on 3 March 1963, Cline wanted to fly home, right away.

Bad weather grounded the flight home until 5 March. About to drive home, to Camden, Tennessee, with friend Dottie West, pilot, Randy Hughes, said the weather cleared enough for the flight. Cline decided to fly.

At a refuelling stop, in Dyersburg, Tennessee, 90 miles from home, the airport manager advised they not continue. The weather, over Tennessee, had turned bad. Still, all aboard the plane wanted to get home.

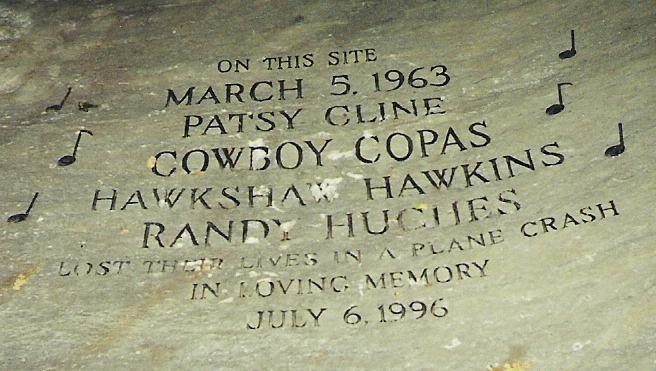

The plane took off, for the final leg of the journey, at 6:07 pm and quickly flew into severe weather. The crash, nose first, killed everyone, instantly. Cline's watch stopped on impact, at 6:20 pm.

Randy Hughes, Cowboy Copas and Hawkshaw Hawkins

Pilot Ramsey "Randy" Hughes, 45, was the son-in-low of Lloyd "Cowboy" Copas, who also died in the crash. At 50, Copas was enjoying a comeback and new hit record, "Alabam." The fourth passenger, Hawkshaw Hawkins, 41, was a member of the "Grand Ole Opry" and husband of singer, Jean Shepard. His biggest hit, "Lonesome 7-7203," released posthumously.

Roger Miller (1936-1992), the country music singer, discovered the body of Cline, in the wreckage. As workers removed the bodies, souvenir scavengers amassed at the crash site. A white chiffon gown, worn by Cline for her last show, disappeared. The scavengers took musical instruments, costumes and whatever memorabilia they might find.

Crash site and marker.

Plane propeller and newspaper black line story

After her death, Cline had three hit singles: "Sweet Dreams," "Leavin' On Your Mind" and "Faded Love." A series of top-selling albums followed. Digitally re-mastered CDs, of all her recordings, will be available in 2010.

The legacy of Patsy Cline continues to grow, unabated. On 4 April 2008, the Virginia Historical Society held a symposium called, "Sweet Dreams: the life and times of Patsy Cline." Bill Malone gave the plenary paper, "Patsy Cline and a Changing South: from depression to postwar affluence."

Her legacy rests on crossover hits, such as "Crazy" or "She's Got You." Few biographies note her 100 or more Country Music records. Patsy Cline was a Country Music singer and a pop superstar.

Brenda Lee likely had more crossover success than did Cline. Their audience appeal was different. Lee had young fans, teenagers who wanted pop 'n' rock; adults liked Cline most.

Brenda Lee, a talented singer, recorded vanilla songs, such as "Jambalaya," or neutral versions, of emotive songs, such as "I Want to be Wanted." Cline, her smokey, sultry and bluesy voice, infused syllables with emotion. Her intensity forced listeners to live the stories she sang; her stories swept past teenagers as fast as a high school History lesson.

Together, her voice and intensity make Cline riveting. A car passes, its radio too loud, but "Walkin' After Midnight" is playing. The rude intrusion gives way to the lyric: "I go out walkin', after midnight; out in the moonlight, just like we used to do. I'm always walkin, after midnight, searchin' for you."

As if sitting across a table, you hang on her every word. Her phrasing, "C-R-a-z-y; for feeling so lonely," pulls you into a story. Trapped, willingly, you understand: "C-R-A-z-y; for thinking that my love could hold you."

On visiting the crash site, where Cline, Copas, Hawkins and Hughes died, Laura Cantrell writes, in Vanity Fair, of a permanent chill. "On a tree stump, beyond the shelter is an improvised shrine, a few stuffed animals, prayer beads, plastic flowers. I stand back in the chilly air, thinking that even in spring, when the woods are waking up; there will be coldness here. It is an awful irony: the warmth of their music can still cut through stereo speakers, their voices and guitars blazing bright, like Christmas fireworks, the reality of their loss weighs heavy like the boulder at the bottom of the ravine: stunning, strange and unmovable."

Virginia Patterson Hensley died in a plane crash, at 6:20 pm, on 5 March 1963. Patsy Cline lives, immortal, in the company of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, among others. Knowing talent impels the memory of Patsy Cline warms the chill.

Jennifer Flaten lives where the local delicacy is fried cheese, Wisconsin. She writes about family life, its amusing or not so amusing moments. "At least it's not another article on global warming," she says. Jennifer bakes a mean banana bread and admits an unusual attraction to balloon animals and cup cakes. Busy preparing for the zombie apocalypse, she stills finds time to write "As I See It," her witty, too often true column. "My urge to write," says Jennifer, "is driven by my love of cupcakes, with sprinkles on top. Who wouldn't write for cupcakes, with sprinkles," she wonders.

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Letter to the Editor

- The No-fly Zone

- Romantic Chocolate Poetry

- Sjef Frenken

- A Third View of Evolution

- A Postage Stamp Bikini

- Stereotyping

- Jennifer Flaten

- Old-fashioned

- The Science Fair

- On the Move

- M Alan Roberts

- Sea Stories 3

- My Bitter Half

- Jellied Brains

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- New Old Car

- Parking Clean Cars

- Rainy Day Off

- Streeter Click

- More Bobby Darin

- Shane McGown Live, Bio

- Look Now, Pay Later

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- An Odd Couple

- Coming Home Empty

- Disastrous Times

- Jane Doe

- Guitar Woods

- Hooters as Work

- Buying an Amp

- M Adam Roberts

- Take Your Shot

- Blind Faith

- I Owe You

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Unicorn

- There is a Light

- Monkey Business