Carly Simon

Jennifer Flaten

Lush, Lyrical and Litigative

Carly Simon and Starbucks seems a heavenly match. Simon oozes warm and cozy. Howard Schultz, who runs Starbucks, oozes charm that disarms, as the stores once did.

The well-honed image, of Starbucks, is the morning after. Middle-aged baby boomers, smugly curled up on a used sofa or in a padded chair, sipping House Blend out of a Venti-sized white-porcelain cup as they chuckle about the personal classifieds in the latest New York "Review of Books." Simon, sensuous and sensual, is the concupiscent night before.

"When I worked radio," says Howard Lapides, of Lapides/Lear, the talent managers based in Los Angeles, "I couldn't wait for a Carly Simon record to come up in the rotation. Okay, the truth be told, I cheated the rotation to get to her faster.

"She's so smooth, smoky and sexy. The good news is Simon still stirs emotions, through her music. I never met her, but all her songs are definitely about me."

As do too many heavenly matches, Simon and Starbucks are in court: she sued it. Her lawyer, David Boies, says, in the New York "Times," the claim is $10 million dollars for "concealment of facts, tortious interference and unlawful, unfair and fraudulent business practices." The sound of a white porcelain mug shattering against a faux-marble floor jolts illusion into delusion.

Starbucks isn't talking. Its silence is deafening. Does the charm of Howard Schultz hide a vain dandy?

In 2007, Alan Mintz headed artist and repertory (A&R) at Hear Music. Hear was the music division of Starbucks. Mintz asked Simon if she'd record an album for Hear.

Hear Music turned "Memory Almost Full," a feeble album by Paul McCartney, into a best-seller. Mintz implied Hear could make her next album her biggest seller. They agreed on a Brazilian flavour, says Simon, and a title, "This Kind of Love."

The album was "My last chance at bat," Simon told Stephanie Clifford, of the New York "Times." Her plan was to record a top-quality album, of her own material: "I wanted to write my last album, rather than record covers"; sell her home in the West Village, of New York City, and move back to Martha's Vineyard, for good. Alas, all lies in hope.

Thanks to Starbucks and financial setbacks, in other areas, Simon must keep working. Her early songs fed on the anxiety of young boomer women. A future album may feed on the angst of older boomers who can't afford to retire.

Her other financial problems are many. The house, on Martha's Vineyard, has a mortgage. She can't sell her West Village apartment. As many, she lost money in the banking scandal, of 2008.

Simon is not alone. Famed photography, Annie Leibovitz, finds herself in similar straits. Leibovitz earns a seven-figure income from "Vanity Fair" and tens of thousands of dollars from clients, but is on the verge of losing most, if not all, of what she owns because of weak financial advice.

Starbucks agreed, with Simon, to a fair deal: an advance, of more than $750,000, when she delivered the final version, of the CD. Simon would pay the recording cost; artists like control.

Starbucks would arrange pressing and delivery of the CDs. Its promotional plan, for the Simon album, was ostensibly solid. All seemed good.

When the contract arrived, her advance fell to $575,000; Starbucks has yet to pay her, in full. Simon is out-of-pocket $100,000 for recording costs. On 24 April 2008, five days before the release of "This Kind of Love," Starbucks closed Hear Music.

The Concord Music Group took over the Simon album. Starbucks released Alan Mintz, not the Simon album. Starbucks also broke a promise to display the album at the cash counter, in each of its 10,000 stores, worldwide, and play her CD constantly in each store.

Through the peak Christmas selling season, for 2009, "This Kind of Love" sold about 175,000 copies. That's about a third of fair expectations. No promotion means a CD is unlikely to get any radio airplay. No radio airplay, no sales and it's about that simple.

Her advance was a prepayment of royalties. If she earns two dollars for each CD, Concord Music has recouped about $350,000. At this point, Simon may owe Concord $200,000, on the advance.

Simon hired Mintz, as her manager, in 2009. The lawsuit followed. She signed to a new label, Iris.

During the ordeal, Howard Schultz, CEO of Starbucks, declined to talk, with Simon. She sent him handwritten notes, keeping copies of each one. "Do you suppose," she wrote, "I would have gone ahead with heavy and visible exposure if I had known I might be dropped in the cracks." A later note was more lyrical: "Howard, Fraud is the creation of Faith and then the betrayal, Carly."

Evidence of deeper, untold problems exists in the deal between Simon and Starbucks. Strange, how no one knew about the 23% drop, in the advance, before the contract arrived. Why did Simon not opt out, of the deal, when Starbucks didn't deliver, as promised?

The ostensibly unannounced change in the agreed-on advance payment was enough to void the offer by Starbucks. Yes, Simon spent $100,000 recording the album, but, surely, she could have shopped the master-tape around. There's more to this deal and the lawsuit than first thought.*

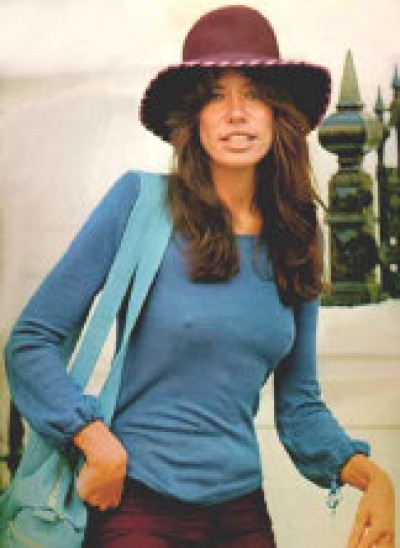

Born Carly Elisabeth Simon on 25 June 1945, she's Sunday's child: sweet, healthy and lively, joyful, cheerful and carefree. Raised in Fiedston, the upper-class part of Riverdale, a middle-class area of Bronx, New York, her mother, Andrea Louise, was an activist and singer. Her father, Richard, was a book publisher and classical pianist.

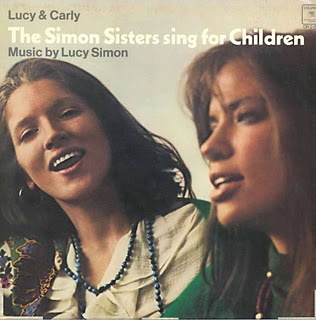

Raised a nominal Roman Catholic, she has two older sisters, Joanna and Lucy, and a younger brother, Peter. Joanna is a former opera singer. Lucy and Carly performed as a duo, in the 1960s. Peter is a photographer, with a studio and store on Martha's Vineyard.

Left: Joanna; mom, Andrea, and Carly, with Peter and Lucy.

Right: Joanna, Carly and Lucy, c. 1949.

Simon attended Riverdale Country School, a tony prep school near her home. After a few months at Sarah Lawrence College, a top liberal arts college, Simon dropped out to chase a music career. During the 1960s, she performed, with older sister, Lucy, as the "Simon Sisters."

The "Simon Sisters" had a minor hit record, in 1964, "Winkin', Blinkin' and Nod." During a show, in Lenox, MA, Simon noticed Odetta, a top folk and gospel singer, her idol, in the audience. "The moment I saw her," says Simon, "I fainted head-on into a table of executives eating pasta."

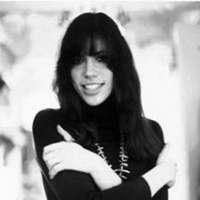

"While growing up," Simon says, "I had such a terrible stutter I was treated like a handicapped child. Now, I write songs and record. Live shows aren't my forte."

After leaving Sarah Lawrence College, Albert Grossman entered her picture. He managed Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, "Blues Project," Paul Butterfield, "The Band," Odetta and many other folk-pop stars. As Lucy O'Brien says, Grossman needed a yin for his yang, Bob Dylan, and tried to groom Simon to fill the role.

Dylan didn't fit well with Simon. Joan Baez, also managed by Grossman, clicked with Dylan, from day one. Baez made Dylan a star, before he dumped her.

Simon was more risque than were most women singers, in the 1960s. She attracted too much attention: at five-foot ten inches, she was far taller than was Dylan. Unlike Baez, she wasn't likely to stand a step behind Dylan, either.

Following a brief stint as singer for "Elephant's Memory," Simon focused on songwriting. She began recording a solo album. Her session players included Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel, of "The Band"; Al Kooper, of "Blues Project," and Mike Bloomfield, of the "Paul Butterfield Blues Band."

In 1971, Electra Records, headed by Jac Hoffman, signed Simon. An eponymous album released. From the album came her first hit single, "That's the Way I've Always Heard it Should Be." She won a Grammy for Best New Artist, in 1971.

After much urging, by her record company, Simon agreed to open for Cat Stevens, at the Troubadour, in Los Angeles. Her anxiety peaked, a few months later, when she headlined at the Troubadour. In 1981, she tried touring, to support a hit single, "Jesse," and album, "Come Upstairs."

She made it about halfway before yielding to her anxiety. "At a show in Pittsburgh," says Simon, "I had a panic attack. I thought I could leave the stage, saying I was suddenly ill, or tell the audience.

"I decided to tell the audience. They yelled, 'Go with it, we'll be with you.' After two songs, the palpitations continued.

"I asked if someone would come on stage, to help me through the panic attack. About fifty people came up. I made it through the show," but that was it; the tour ended in Pittsburgh.

In retrospect, she says, the idea of touring in 1981 was foolish. "My marriage, to James Taylor, was breaking up. My son, Ben, was ill and had a kidney removed. I lost 25 pounds; I weighed 112. I was in terrible shape."

Simon dated Cat Stevens for about seven months, in 1971. Their first date inspired her second hit, "Anticipation," from the album of the same name. The title may as well been "Anxiety": "We can never know," she wrote, "about the days to come, but we think about them anyway."

In her personal life, Simon has a taste for strong, successful men. Before her marriage to then drug-addled James Taylor, her list of lovers included Warren Beatty, Mick Jagger and Kris Kristofferson as well as Cat Stevens, among others. Each of these men is a vain dandy.

Simon wrote best about what she knew. She knew vain men. Not a surprise her next hit, her biggest hit, was "You're So Vain," from her "No Secrets" album.

"You're So Vain," begins with a breathy, low frequency line, "Son of a Gun," then moves on to the lyric. Everyone knows the phrase is a euphemism for bastard. Radio listeners didn't hear her say the line: on a 45-rpm disc, it didn't broadcast, well.

Radio stations quickly transferred "You're So Vain" to tape. When the tape aired, "Son of a Gun" came across, clearly. A good pop song, the success of "You're So Vain" was partly a result of the naughty opening phrase.

Success for "You're So Vain" was also partly due to the lyrical focus. Everyone knows a haughty, selfish and sneaky person or ten. Simon wrote what each of us knows, too well and too often.

The common central character offers the best clue to her muse for this lyric. Although Simon talks freely about her lyrical inspirations, such as James Taylor for "You Belong to Me," she's mum about "You're So Vain." There's nothing for her to say, the lyric isn't about any one person, but many.

Watch Warren Beatty walk, in any movie, and it's easy to imagine him walking into a party as if he were walking on to a yacht. Mick Jagger often wears an apricot scarf. Hugh Heffner, of "Playboy" magazine, is always in the right spot at the right moment.

The list of likely muses might include her father, Richard L. Simon, every male at the Riverside Country School, Paul McCartney or Richard Simmons. Only the late author, Truman Capote, fits all the metaphors, including "with some underworld spy or the wife of a close friend." He was openly gay and an unlikely muse, for "You're So Vain," unless the lyric is satirical.

In 2003, Simon almost revealed her muse for "You're So Vain." She offered the information for a charity auction. She had one condition: the winner could not reveal what Simon wrote and said.

Wrote and said? Simon wrote part of the answer to the question, about her muse for "You're So Vain," on a small piece of paper. As she handed the paper to the winner, Simon whispered the rest of the answer, softly into his ear. Some fellow paid $50,000 to keep her secret: good grief.

Simon recently told "Uncut" magazine, "You know what, I'm just going to tell you this -- the answer is on the new version of "You're So Vain,", on my new record "Never Been Gone." There's a little whisper and [the name] answers the puzzle." The name is pronounced backwards, Divad; elsewhere, on the album, the name of another muse, for the song, is quietly whispered.

Her clue, a non-clue, in fact, appears about 2.5 minutes into the new version of "You're So Vain," if you listen to the cut backwards, and only narrows the possibilities. In 2003, Simon titillated fans claiming the letters "A," "E" and "R" were in the name of her muse: everybody was sure Sir Mick JAggER was the one; maybe WArREn Beatty or TRumAn CapotE. Now, Simon now seems to rule out Jagger, Beatty, James Taylor, Cat Stevens and Howard Lapides, among others.

If the letter clues jib with the name clue, her possible muses, for "You're So Vain," reduces to a handful. One, of the fewer possibilities, has long been the choice of music industry insiders. Still, it's easily a fellow from Riverside Country School.

Just prior to the release of "Never Been Gone," rumours circulated that David LAwRencE Geffen, once head of Asylum Records, was the muse. Apparently, Simon was upset Geffen was promoting Joni Mitchell more heavily than he was promoting her. "Geffen and Simon locked horns about 1974 or 1975," says a insider who adds, "I don't want my name associated with her [Simon] scam to sell records.

Simon has said, all along, she wasn't upset, with Geffen until at least 1974, two years or so after "You're So Vain" released. On 26 February 2010, a spokesperson, for Simon, was adamant Geffen was not the the must for the song.

Geffen is also openly gay and the muse for "Freeman in Paris," by Joni Mitchell. "Didn't 'The Beatles' pull the same stunts 45 years ago," says the insider, "when it was fresh." On 1 March 2010, Simon told 411mania, "What a riot! Nothing to do with David Geffen! What a funny mistake! Someone got a clue mistaken for another mistake!"

Simon needs to sell records, given her comments surrounding the deal-gone-bad with Starbucks. It's easy to decide she knows how to milk the buzz dry. The best guess remains, "You're So Vain" is about a number of her lovers, as Simon said in 1989, not one; maybe Geffen is one of the many, but not likely.

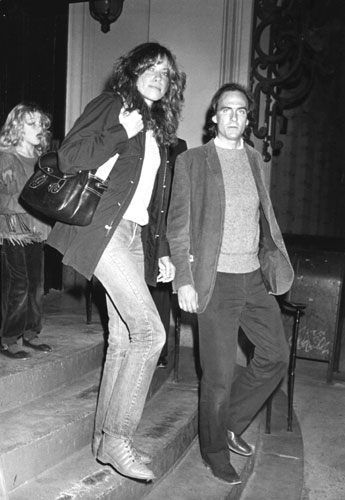

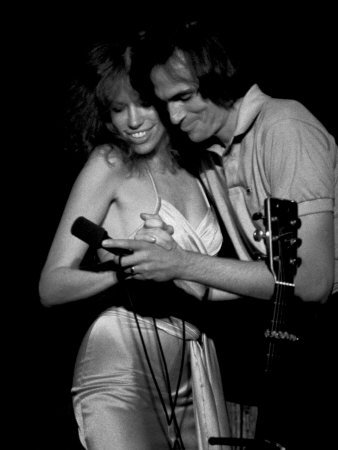

Allegedly, Simon lured James Taylor away from Joni Mitchell, thus, "You Belong to Me." Taylor and Simon were getting it on in a washroom, says Sheila Weller, ten minutes after they met. They married on 3 November 1972.

In 1974, Electra Records merged with Asylum Records; David Geffen took control of the recording career of Carly Simon. "Carly released another album, called 'Hot Cakes,' on Elektra, says Roger Friedman, of ShowBiz411. "Joni Mitchell released 'Court and Spark,' at the same time. 'Freeman in Paris,' inspired by Geffen is on the Mitchell album.

"Simon felt Geffen gave more attention to Mitchell. She was upset." Nice payback for Mitchell.

Simon and Taylor have two children: Sarah "Sally" Maria and Benjamin. Both are musicians. Ben owns Iris Records, for which his mother now records and where she finds renewal, if not solace, in her older material.

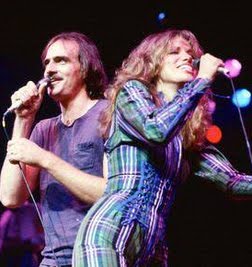

During the 1970s, Simon sang back up on recordings by James Taylor. She sang on "One Man Parade," "Rock 'n' Roll is Music Now," "Let It All Fall Down" and "Terra Nova," among others. They had a hit duet, in 1974, with "Mockingbird."

"I have always suffered stage fright," says Simon. "When James Taylor and I used to sing "Mockingbird," together, I forgot all about fright of any kind. Happiness is hitting the right notes with the man you love"

Simon and Taylor spent eleven tumultuous years trying to stay together. "Couples cling and claw and drown in love's debris," she wrote, in "Let the River Run." The song, from the movie, "Working Girl," won her the 1989 Academy Award in the Best Song category.

"Today, we don't speak, much," says Simon, of her and Taylor. "We do share Sally and Ben, though." Her marriage to Taylor is a cloud in her coffee.

Simon appeared on "Saturday Night Live" (SNL), in 1976. Musical segments, of SNL, pretape; her stage fright wasn't an issue. During her performance, of "You're So Vain," SNL regular, Chevy Chase, joined her vocal back up group, wearing an apricot scarf and acting as a vain dandy.

Albert Broccoli asked Simon to write the theme song for a "James Bond" movie, "The Spy Who Loved Me" (1977). She wrote "Nobody Does It Better." She mentions the movie title once, in her lyric: "but like heaven above me, the spy who loved me, is keeping all my secrets safe tonight."

"Nobody" was a huge radio hit, peaking at number two on the "Billboard Hot 100." The first verse sold the song: "Nobody does it better: makes me feel sad for the rest. Nobody does it half as good as you, baby you're the best." How many ways can she write, "You're So Vain."

The 1980s were a low time in her career. Simon recorded a series of good albums that didn't sell. "I prefer to write and record, but not perform," Simon said, "and if I don't perform, my albums don't sell as well as possible."

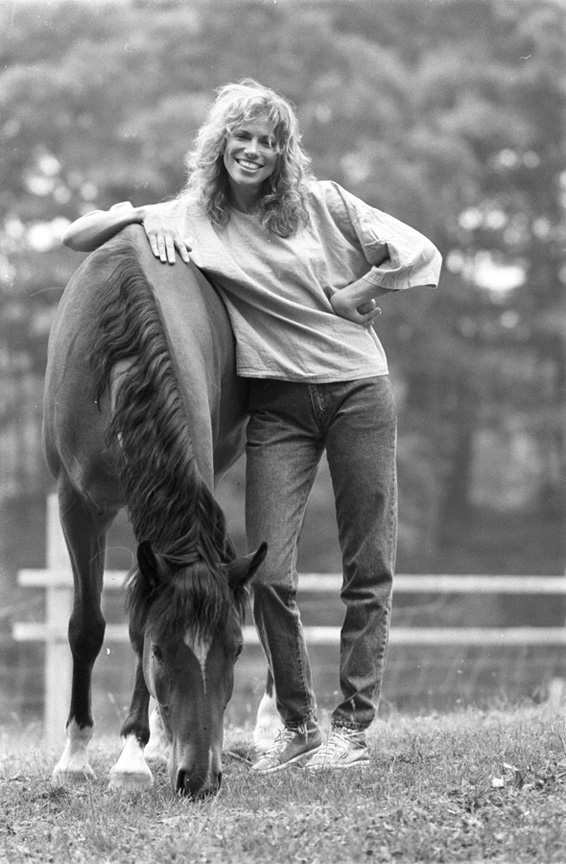

In 1986, Simon performed, live, twice, on consecutive nights, at Gay Head, near her home on Martha's Vineyard (below). The first show, at twilight, was a run through for an HBO special. The second show taped for HBO, as "Carly in Concert: coming around again."

Simon seems weary, on the HBO special, but not anxious. She sings with elan, appearing relaxed and at ease, thoroughly enjoying herself. Still, appearances usually deceive.

In the late 1980s, Clive Davis convinced Simon to sign with Arista Records. Radio rediscovered her. The first Arista album, "Coming Round Again," though Maudlin: tear-sopped lyrics about early loves and easy loving, as a hit. The airplay led to several albums that sold well. She was a top-tier recording star, again. Simon also overcame her performance anxiety, enough, to tour, in 1995, with "Hall and Oates."

Simon wrote several books for children, in the 1990s: "Amy the Dancing Bear," "The Boy of the Bells," The Fisherman's Song" and "The Nighttime Chauffeur." For an album, "Mother Goose's Basket Full of Rhymes," Simon set nursery rhymes to music. Her last book for children, "Midnight Farm," lends its name to a store she owns on Martha's Vineyard.

Simon pines for her home on Martha's Vineyard. The island, off the east coast of Massachusetts, was once a summer colony for the wealthy or artistic. in 1975, after the movie, "Jaws," filmed on the Vineyard, it became a tawdry tourist trap, crammed with day trippers, craning to see the grave of John Belushi or catch a glimpse of a resident celebrity. Today, it's hard to imagine anyone pining for home on the Vineyard.

Still, the Simon home is different. Her home is her family home, nominally shared with her siblings, today and during childhood. Most important, her home is safe haven, subtly secluded.

The Simon home is one of about forty, in a small development. Designed, in part, by her father, Richard, more than fifty years ago, no home, in the development, can see any other home. He had a unique and lasting appreciation for privacy.

A lyric is a brief poem. It expresses personal feelings and is for singing or silent reading. When she wishes, Simon has full, innovative command of this skill.

A melody is a rhythmical succession of single tones. A melody forms a musical phrase or idea. At her best, Simon has passable command of this skill.

Not surprising, lyrics come first for Simon. She's a librettist, telling stories, set to music, that most anyone understands. Her legacy lies in timeless lyrics, not tired melodies.

Starbucks welching on Simon seems more a poke in the eye, an assault on her status; for Simon, it's likely less about money. She likely pocketed fifty thousand from the adjusted deal. The lawsuit is unlikely to add much, unless Starbucks yields too soon, which isn't likely.

The poke in the eye is partly unrealistic hope. Starbucks offered "too good" a deal: Starbucks would make Carly Simon an impulse item. She got caught, hook, line and sinker; heart and soul.

The potential, as an impulse item, was overdrawn. A greatest hits CD might make a good impulse item. A Brazilian-flavoured CD, from Simon, is more for the seasoned connoisseur of Simon.

Lucy O'Brien says Simon is an inconsistent songwriter, but "an arch manipulator of image." Her coyness about the muse for "You're So Vain" is a good, if trite, example. Simon sees herself as pop royalty; she expects treatment according to her self-perception and Starbucks didn't go along.

For Simon, Starbucks treated her in an unbecoming way; maybe it let her think a Brazilian-flavoured CD was as much an impulse buy as a greatest hits CD. She's insulted and wants her way. Lucy O'Brien decides that Simon is a poor little rich kid.

It's difficult to concede Simon is not wealthy or, at least, well-off. "People think I'm an heiress," she told the New York "Times," in 2009. "I inherited $60,000 of what my father got when he sold Simon and Schuster."

"Until my father passed away, in 1960," says Simon, "you might say I lived a privileged life, of a sort. He left me some money, which I spent on psychiatric help, trying to discover why I thought I was a mess. From about age 19, I lived hand-to-mouth. "

Well, yes, there's Simon and Schuster, the huge publishing house her father started and sold. There's Fiedston, a la-tee-da neighbourhood in the well-heeled area of Riverdale. There's Sarah Lawrence College. There are a great many hit songs, written and recorded; millions of records sold. All that's missing is the biggest source of income for entertainers: touring.

Simon works harder than do many entertainers, but her rewards are less than most. Over the past forty years, she likely grossed about forty million dollars from writing and recording. Out of her gross, Simon paid a manager, maybe an agent, a lawyer, maybe a publicist, the cost of recording, other related expenses and taxes.

Donald Sutherland, the actor, says he's happy if he takes home ten per cent of what he makes for a movie. Much the same applies to Simon. By fair estimate, she took home four million dollars over forty years or one hundred thousand a year.

Simon took home a lot more money than did most of us, but hardly as much as she might. A touring band, think of one, might do fifty shows over thirteen weeks. Its gross might easily run to thirty million dollars. Each, of five members, can take home about three hundred thousand dollars or more.

A touring act can do this, if not every year, than every eighteen months. Add to its earnings, royalties from a new CD and catalogue CDs, endorsements, soundtracks and so forth. Simon draws only on the last few sources of income as well as writer royalties.

"The Rolling Stones," Elton John and "U2" do much better than the example; many acts don't do as well. The point lingers, Simon was unable to tour, it dramatically cut into her earnings and, today, she likely needs to work. Too many baby boomers find themselves in the same crisis.

Gauged against her the money made over her career, say, forty million dollars, the Hear Music fiasco is a trifle. Considering her most likely take-home pay, say, four million dollars, over forty years, the lost money is a huge dent; damage to her repute and prospects make the loss significantly larger. Starbucks, always honing its fair play image, welched; this makes the circumstance worse, again: it's not what she believed about the company or Howard Schultz.

A "You're So Vain" tour would gross two hundred million dollars, over two years. She can't do it, for fair reasons. The enormous stress would undermine her health, in the end making everything worse. Many women and men can't work or work full-time for similar reasons.

The lawyers, on both sides, will find mutual satisfaction. When the legal costs reach a certain point, Starbucks will settle. It'll pay all the legal costs and Simon will get a dollar.

A dollar is what Starbucks CEO, Howard Schultz earns, a dollar a year for each store. That's about ten thousand dollars a year, plus the profit from a 150 or so stores he owns, outright, and his stock in Starbucks. Someone said, if Schultz piled his share certificates, one on top of the other, and he sat on the top of the pile, gawd could consult, more directly, with him.

Simon has her agenda. Sadly, it seems mostly a cry for renewed attention; more about status repair than tortious acts. Health issues and other financial problems add to her plight, but the same forces effect most everyone.

John and Jane Doe pick up the pieces and move on. Simon, it seems, is trying to do the same. Still, going public, with the lawsuit and agreeing to do degrading media interviews about it, seems more harmful to her career, repute and prospects than does quietly settling the matter.

Simon picks up the pieces trying to tour. Ostensibly, in January 2010, she gave a series of intimate shows in Europe to promote a new album, "Never Been Gone." Overcoming stage fright and her morbid fear of flying, at the same, seems a major challenge, more damaging than expected.

There's nothing on her official site about a tour. Nor is there any web buzz about the tour. "OK" magazine seems the sole source of this rumour.

In the end, Simon is an entertainer. She writes likable melodies and provocative lyrics. Her body of work distracts us, if only for a moment; helps us recall a happy memory or forget the travails of the day: that's how it should be or so I hear.

-------------

*Los Angeles District Court Judge, George Wu, dismissed the suit again Starbucks brought by Simon, 20 April 2010. Judge Wu ruled Starbucks did not violate any duties to Simon by closing its music division, Hear Music, five days before the scheduled release of her album. Simon contracted to Hear Music, a company separate from Starbucks, which went out of business. She thus had no claim against the coffee chain.

On 31 May 2010, Simon refiled her lawsuit against Starbucks. She claims a lack of promised and adequate promotion of her 2008 cCD "This Kind of Love." The up-dated lawsuit asserts Alan Mintz, then vice-president of Content Development for Starbucks, promised in person and during phone calls her CD would be widely promoted and distributed by Hear Music, the record label owned by the coffee chain. After leaving Starbucks Mintz became the manager of Simon; his current status is unclear.

Stephanie Clifford (2009), "Suing Her Label, Not Retiring: Carly Simon won't go gently," in the New York "Times," for 11 October; page C1.

Stephan Holden (1987), "Carly Simon Triumphs Over Her Own Panic," in the New York "Times," for 17 June 1987; page C19.

Lucy O'Brien (1995), "She Bop," published by the Penguin Group.

Sheila Weller (2008), "Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon and the Journey of a Generation," published by Atria Books.

Jennifer Flaten lives where the local delicacy is fried cheese, Wisconsin. She writes about family life, its amusing or not so amusing moments. "At least it's not another article on global warming," she says. Jennifer bakes a mean banana bread and admits an unusual attraction to balloon animals and cup cakes. Busy preparing for the zombie apocalypse, she stills finds time to write "As I See It," her witty, too often true column. "My urge to write," says Jennifer, "is driven by my love of cupcakes, with sprinkles on top. Who wouldn't write for cupcakes, with sprinkles," she wonders.

- Book 'em

- The Agogny of the Artist

- De-christmasing

- Car Ride

- What on a Stick?

- Respectfully Yours

- Hockey Mom

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Bacongate

- Identity Missed

- Faith-based Sports

- Sjef Frenken

- A Way with Words

- Dumb Whales

- Democracy Covered

- Jennifer Flaten

- Reunited

- Supply Closet

- Fish Business

- M Alan Roberts

- Cries of Rebellion

- Health is Wrong Here

- Ants at the Picnic

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Long Distance

- Fall 2017 TV Review 1

- Travelling Bananas

- Bob Stark

- Follow the Money

- After the Deluge

- Canucks Win Cup

- Streeter Click

- Look Now, Pay Later

- WNBC, c1980

- Tanna Frederick

- JR Hafer

- Rosko

- The Special Birthday

- WNEW Radio

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Pass and Repeal

- Blown Away by Bob

- Hidden Treasure

- Jane Doe

- Mrs Doubtfire

- Dominion

- US Debate 1 2016

- M Adam Roberts

- The Nite Busker: 2

- Essence of a New Day

- Learning to Fly

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Harmony

- The Unicorn

- There is a Light