Stonewall at Fifty

RK Samuelson

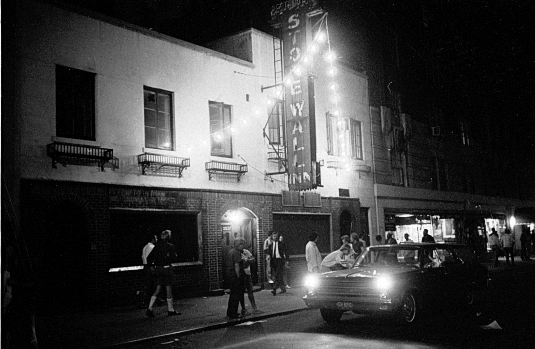

“Early in the morning of [28 June] 1969,” writes Kwame Anthony Appiah, (in the New York Times, 22 June 2019), “police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in … Greenwich Village … this time the patrons didn’t go quietly. A mutiny against police harassment erupted and spread; street rioters even set the bar on fire.”

► Gangsters owned the gay bars

Mobsters owned most or all of the gay bars and clubs in New York City. Fat Tony, of the Genovese family, owned the Stonewall Inn.* A run down, out-of-business restaurant was the ideal location for a gay bar.

Walls and windows painted black and a burly attendant g guarding the door, Stonewall was a private club for drinking and dancing. It was private because a liquor licence was impossible for such bars. Under-age patrons were many and thus enough reason for random police raids; the presumed degenerate lifestyle of found-ins justified use of excessive forced.

That Friday night, in June 1969, the Stonewall Inn was the site of a symbolic breakthrough for gay and lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) rights. The raid was a typical, opportunistic police action against a New York City club patronised by what the LGBTQ community. It was an election year and candidates for municipal office liked to run on the image of a clean city.

Female police officers escorted cross-dressing patrons into a bathroom to verify their sex. Thirteen people arrested for violations of the New York Stage Gender-appropriate clothing statute. It would be funny, if not extremely serious and dangerous.

The police took names and the news media took photographs, both published, usually the next day. Anyone reported, by the news media, was liable for dismissal from his or her job. It was legal and happened all the time.

Patrons, of the Inn, faced off against overly rough police, in a meaningful way; there was much at stake. Residents of the neighbourhood did not take kindly to what was happening, either. Instead of leaving, they stayed; they waited. “An act of resistance became a flashpoint in the struggle for [LGBTQ] dignity and equality,” writes Appiah.

As a police officer forced a lesbian into a paddy wagon, he hit her on her head. She screamed for help. On-lookers threw pennies and bottles at the police; soon a full-blown riot erupted.

As police tried to find safety in the Stonewall Inn, the building was set on fire. The fire department doused the flames. Those inside the building were rescued and the crowd, eventually, dispersed.

The rioting continued on Saturday night, lasting six nights longer. LGBTQ citizens would no longer stand down and take what the police inflicted; they fought back. Symbolically, this event drove the LGBTQ rights movement into public view. It was a remarkably long time coming, but had arrived; it would not go away.

► Transgender women are the heroes of Stonewall.

Unlike the mainstream LGBTQ rights organizations, which exist today, directed by white, cisgender men, Stonewall was an anomaly. Two transgender women were behind the Stonewall riots. Sylvia Rivera (1951-2002) was a gay liberation and transgender rights activist; Marsha P Johnson (1945-2992) was a founder of the Gay Liberation Front.

Together, Rivera and Johnson co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). This organization fights for the rights and protection of homeless queer youth as well as sex workers. The efforts of these activists are remarkable.

Statues of Rivera and Johnson, to honour their exceptional efforts, will soon to stand in a public square near the Stonewall Inn; the exact location is undecided. When he announced the statues, New York City mayor, Bill de Blasio, said, “Transgender and non-binary communities are reeling from violent and discriminatory attacks across the country. [In] New York City, we are sending a clear message: we see you for who you are, we celebrate you and we will protect you.”

► Change came slow but sure.

The fall out of Stonewall was slow but sure. In 1980, the New York state Supreme Court made same-sex sexual activity, among consenting adults, legal. This was a historic decision, but late in the game, as Canada and the UK enacted similar laws in the late 1960s. It was a significant start, though.

In 1998, there was a legal ban on discrimination based on sexual orientation. As of 2019, the ban extended to gender identity and expression. In 2011, New York became the sixth state in America to legalize the marriage equality act.

Other LGBTQ activists are following in the footsteps of the brave LGBTQ that took to the streets in 1969, not allowing it or the cause to leave social memory. They write of it in magazines, Facebook articles; they hold rallies and march in parades. They keep the story, the history, alive and vigorous for the LBGTQ community and its supporters, today.

In 2016, then-President Barack Obama designated the sights of the riots, including the Stonewall Inn and Christopher Park, as national monuments. These are places to visit and remember for historical effect. These places played important roles in the advancement of LGBTQ and human rights, generally.

► NYC matures into a LGBTQ friendly city.

In 2019, New York City began to celebrate its LGBTQ history. Commemorative statues, organizations to help and protect LGBTQs as well as banning activities, such as conversion therapy, are important steps in the direction that started in 1969, at the Stonewall Inn. The New York City Police (NYPD) apologized for the 1969 Stonewall riots in June 2019. The NYPD, which just fifty years ago, stormed gay bars and acted violently, now walk alongside and among LGBTQ in gay pride parades; government is slowly changing its stance, too.

The violence and discrimination against the LGBTQ community hasn’t ended and likely won’t for a long time. The tendency, though, is definitely in the right direction. In 2017, a public religion research poll found more than two-thirds, of New York City residents, supported same sex marriage, whereas less than one-in-four opposed it.

New York City, now, is one of the most LGBT-friendly cities in the US. This is a remarkable change growth from just fifty years ago, when police raided that small bar in Greenwich Village. Today, the NYC LGBTQ community flourishes.

The Stonewall riots weren’t solely for gay rights, but for a new awareness. Too often, discrimination was based on accidents of birth, who one loved or what gender they believed there were, inside. The riots were a fight against the denial of rights for all, including women, Blacks, gays and other minorities and disenfranchised groups.

Minds are opening. People are not as afraid of the new or unknown. As long as we tell the story of Stonewall and don’t forget history, tolerance of differences will morph into acceptance.

► The memory can’t fade.

The events of 28 June 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, in New York City, eventually influenced society, not only a sub-culture or two. Still, it was the beginning of fights for rights. The causes must not slip from memory and fights must continue.

-----

* Michael Wilson, “The Night the Stonewall Inn Became a Proud Shrine,” in New York Times, 27 June 2019.

Robert King Samuelson, in his own words, "is a perspiring writer trying to raise his voice above the cackling insolence and fractured language of the bloggery."

- Curse of Laboriousness

- The GOP as Faust

- What Trump Teaches

- Impeachment May Help Trump

- Stonewall at Fifty

- Crises in America

- Human Costs of Crime

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Word of the Year 2017

- Orphan Sock Policy

- Best Political Team

- Sjef Frenken

- Multiple Choices

- Dogs, Cats and Tofu

- Art and Mammon

- Jennifer Flaten

- Linen

- Techie No-no

- Christmas so Soon?

- M Alan Roberts

- Sea Stories 2

- Brain Abusers

- Wild Horses

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Owners and Players

- Coffee

- Moving

- Streeter Click

- Police Drama of 1950s

- Reel Guys Reviews

- Best of the Best

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- A Skype Wedding

- The Egyptian

- Writing and Passion

- Jane Doe

- A Coffee Mug

- US Debate 1 2016

- Char-broil 480

- M Adam Roberts

- Lazy Bones

- Son of a Gun

- The Visitation

- Ricardo Teixeira

- There is a Light

- Harmony

- Monkey Business