Saved from Chaucer

David Simmonds

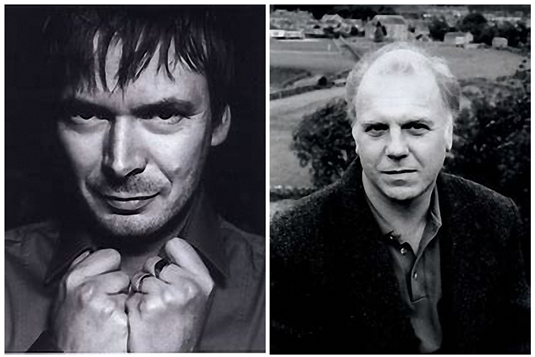

Ian Rankin, left, and Peter Robinson.

Is the weather crazy in Wellington County or what? It warms up just enough to turn the ice to pools of water, but not enough that the water drains away. Then it freezes over and you’re stuck with massive new ice patches.

► Climate change in action.

Next, it snows, meaning you have to shovel in order to maintain access to the outside world. All that accomplishes is to uncover the ice again, offering new opportunities for you to slip and break your clavicle. Then the cycle repeats.

You’re stuck inside, with cabin fever. At such a time, I’m delighted to turn to the Wellington, Ontario, branch of the Prince Edward County Library (PECL) to help me through. For example, I’m able to enjoy the well-crafted memoir, Becoming, by Michelle Obama; it’s much more inspiring than the latest Trump takedown. In fact, I’ve sworn off Trump disaster books; what’s the point in feeding my rage?

I haven’t had to reach into the classics, such as Homer or Chaucer, yet. That’s because one of my guilty reading pleasures is the detective novel. I was thus delighted to devour, guilt free because of the weather, new books by my two favourite genre writers; Ian Rankin, author of In a House of Lies, and Peter Robinson, author of Careless Love.

Rankin is a Scot. Robinson, who grew up in England, resides in Canada. Each has been at it non-stop since 1987.

The most recent Rankin book is the twenty-second in his series, featuring recently retired police officer, John Rebus, and set in Edinburgh, Scotland. The new book by Robinson is the twenty-fifth in his series, featuring inspector Alan Banks and set in the Yorkshire Dales. When I say, set, I really mean it. You could just feel yourself sitting watching the action from a ringside seat in a local pub.

These writers have each won multiple crime writing awards. Each had their works turned into television series. Rankin and Robison have earned their spurs.

As I read these two new books almost back to back. The similarity, in their principal characters, Rebus and Banks, struck me. Each character is a loner, not particularly inclined to do things by the book, with a poor regard for his own health, but with a well-developed sense of the superiority of his taste in 60s and 70s UK pop music; a taste that he doesn’t hesitate to inflict upon others. Mind you, I can’t picture a successful fictional detective with a taste for bubble gum music.

► Anti-bureaucratic, lone wolf officers.

Each also has a failed marriage. Each has mentored a junior female officer, Siobhan Clarke for Rebus and Annie Cabot for Banks, that has risen in responsibility despite personal hardship. The almost anti-bureaucratic, mostly lone wolf police officer is ready to help others to the top.

After turning out forty-seven books and that’s just the Rebus and Banks output, between them, you would think the well of inspiration would be running dry for Rankin and Robinson. That is not the case. Both new books are an all-consuming read. Indeed, the plots promise more to come.

Rebus still hasn’t wrestled his nemesis, Big Ger Cafferty, to the ground. Banks has unresolved issues with.an attempted murderer spotted in sinister company.

How do the two novelists maintain their edge? Aside from coming up with a strong plot, which must get more difficult each time, they keep up with technology. They also allow their characters age in real time, thereby forcing new personalities into the story.

In addition, neither Rebus nor Banks is limited to the sort of storyline in which, with all the suspects assembled, the detective demonstrates his brilliance by showing how he has deduced that the butler is guilty. Nor does either book end with the villain desperately chased by the hero, who takes the villain down in a heart-stopping one on one showdown. Rankin and Robinson are prepared to focus on the why of the crime or the how of its solution at the expense of cheap, largely ineffective action.

Rankin is particularly strong at capturing quick-paced dialogue. The strength of Robinson lies in giving a reasonable explanation to the seemingly inexplicable scenarios confronting his detective. More writers of detective fiction should take note of these strengths.

► Are Homer and Chaucer as entertaining as are Rankin and Robinson?

My hat is off to Rankin and Robinson for the entertainment they provide me. Let me plead with them: if the weather next winter is going to be anything like this year, please have your next tomes published by fall. I wouldn’t really like to count on Homer or Chaucer to entertain me.

Some readers seem intent on nullifying the authority of David Simmonds. The critics are so intense; Simmonds is cast as more scoundrel than scamp. He is, in fact, a Canadian writer of much wit and wisdom. Simmonds writes strong prose, not infrequently laced with savage humour. He dissects, in a cheeky way, what some think sacrosanct. His wit refuses to allow the absurdities of life to move along, nicely, without comment. What Simmonds writes frightens some readers. He doesn't court the ineffectual. Those he scares off are the same ones that will not understand his writing. Satire is not for sissies. The wit of David Simmonds skewers societal vanities, the self-important and their follies as well as the madness of tyrants. He never targets the outcasts or the marginalised; when he goes for a jugular, its blood is blue. David Simmonds, by nurture, is a lawyer. By nature, he is a perceptive writer, with a gimlet eye, a superb folk singer, lyricist and composer. He believes quirkiness is universal; this is his focus and the base of his creativity. "If my humour hurts," says Simmonds,"it's after the stiletto comes out." He's an urban satirist on par with Pete Hamill and Mike Barnacle; the late Jimmy Breslin and Mike Rokyo and, increasingly, Dorothy Parker. He writes from and often about the village of Wellington, Ontario. Simmonds also writes for the Wellington "Times," in Wellington, Ontario.

- Casseroles Break Up

- Political Slogans

- The Bagpipe Incident

- Over the Quarter Moon

- Entering the Lexicon

- Funny at the Time

- Saved from Chaucer

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Explosive Campaign

- Casseroles Break Up

- Timbit Diplomacy

- Sjef Frenken

- Streamlining the World

- Finis

- Verbal Widdershins

- Jennifer Flaten

- Baby, It's Cold Outside

- De-christmasing

- Mysophobia

- M Alan Roberts

- Checkmate

- Brain Pump

- I Got Crabs

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Vacation 2015: 1

- Thinking of Death

- Recent Audio History

- Streeter Click

- Junos Boring, Always

- GrubStreet Mileposts

- More Bobby Darin

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Act One

- Paper Patterns

- Finding the Idea

- Jane Doe

- Del Shannon "Runaway"

- A New Day

- Buying an Amp

- M Adam Roberts

- Lazy Bones

- Humble Pie

- Is She the One?

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Future

- Monkey Business

- Harmony