Outraged Grammarians

David Simmonds

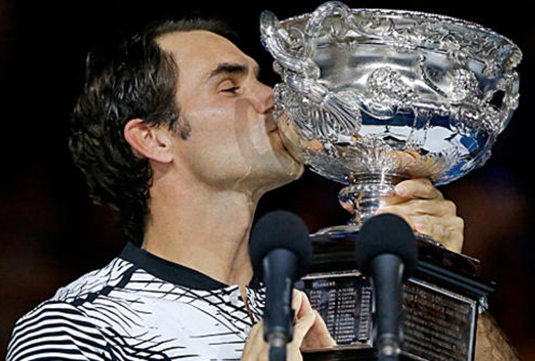

I was going to write about grammar this week. Then Roger Federer won the Australian Open men’s singles title for the sixth time, to bring his tally of Grand Slam titles to an even twenty. His feat deserves recognition. I decided to combine grammar and Federer.

What am I after on the grammar front?

This time, I’m after words and phrases that sound important, but float away like dandelion fluff on the most casual analysis. Take this statement, for example, “When all is said and done, Roger Federer will be remembered as the greatest tennis player of all time.” What exactly does “when all is said and done” add to the point being expressed; nothing.

Anyone that purports to choose the greatest player of all time and wants his or her opinion taken seriously must take into account every relevant thing that said and done, ever. After all, “all time” has a long while to go. It isn’t over when Federer quits playing competitive tennis.

It would be simpler to say, “In my opinion, Roger Federer is the greatest tennis player of all time.” Simpler, but not simple enough, I say. There is no UN appointed International Court of Tennis Greatness, so any statement comparing past and present as well as future players, if one is to be logically correct, is bound to be a matter of opinion. It’s unnecessary to add the qualifying phrase, “in my opinion,” or any similar concoction such as, “so far as I’m concerned,” “for me, personally,” “from my point of view” or “from where I sit.”

Once you recognize a filler phrase, it becomes easier to spot others. Take “for better or worse,” “all things considered,” “at the end of the day,” “all in all” and “on balance.” Each phrase is just a way to stretch and thereby weaken the point with a false gravitas.

Wait, there’s more.

“In the process of” should usually fall victim to the pent of an editor as should “in the event that,” “for the most part” and “for all intents and purposes.” These phrases add nothing but fluff. I was going to add “needless to say” to that list, but decided that it must be acceptable; otherwise, why would I have used it in my column last week?

Then there are the expressions that project the sense that the speaker is drawing on a special fund of personal honour; phrases such as “to be honest,” “frankly,” “literally,” “as a matter of fact” and “in a very real sense.” The trouble with using those expressions is that when you don’t employ them, you invite the listener to consider the possibility you are being dishonest or less than candid. You would be better off adding the filler to every assertion you make; better off, still, dropping it and letting the listener assume that you are always honest and candid.

Filler words cover for us when we are afraid that simple and direct language will reveal that we don’t have that much to say. Simple and direct is harder to misinterpret. Most often, we’re better off without the filler.

I admit, though, there are occasions on which a little fluff is needed. For example, if I were holding court in a bar in Melbourne I would not to go for the grammatically spare, but highly provocative assertion, that “Roger Federer is the greatest tennis player of all time.” I would instead lace it with filler, such as “At the end of the day, all things considered and on balance; for me, personally, Roger Federer is the greatest tennis layer of all time.” That would give me a few extra seconds of opportunity to make it to the airport before an angry mob of Rod Laver fans took my hide.

A posse of outraged grammarians.

Whether I could also make it with a posse of outraged grammarians in hot pursuit is a question that will go unanswered. Truthfully, I hope never to find myself in that predicament.

Some readers seem intent on nullifying the authority of David Simmonds. The critics are so intense; Simmonds is cast as more scoundrel than scamp. He is, in fact, a Canadian writer of much wit and wisdom. Simmonds writes strong prose, not infrequently laced with savage humour. He dissects, in a cheeky way, what some think sacrosanct. His wit refuses to allow the absurdities of life to move along, nicely, without comment. What Simmonds writes frightens some readers. He doesn't court the ineffectual. Those he scares off are the same ones that will not understand his writing. Satire is not for sissies. The wit of David Simmonds skewers societal vanities, the self-important and their follies as well as the madness of tyrants. He never targets the outcasts or the marginalised; when he goes for a jugular, its blood is blue. David Simmonds, by nurture, is a lawyer. By nature, he is a perceptive writer, with a gimlet eye, a superb folk singer, lyricist and composer. He believes quirkiness is universal; this is his focus and the base of his creativity. "If my humour hurts," says Simmonds,"it's after the stiletto comes out." He's an urban satirist on par with Pete Hamill and Mike Barnacle; the late Jimmy Breslin and Mike Rokyo and, increasingly, Dorothy Parker. He writes from and often about the village of Wellington, Ontario. Simmonds also writes for the Wellington "Times," in Wellington, Ontario.

- Saved from Chaucer

- An Avalanche of Drivel

- Reality Olympics

- Plurality of Cynics

- Revising Oh Canada

- Obits Blitz

- The Phase Phase

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Self-defining Words

- Plurality of Cynics

- Net Negative

- Sjef Frenken

- Dog Heaven

- Ultima Thule

- New Words Defined

- Jennifer Flaten

- Cheesburger, please

- Car Love

- Rice

- M Alan Roberts

- Tiny Teachers

- A Loveless Life

- Rat Racing

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Oscar and the Pigeons

- Dealing with Back Pain

- Long Distance

- Bob Stark

- Murder Most Fowl

- Ozymandias

- Say It Ain't So

- Streeter Click

- Beaver Does Broadway

- The Master Dedective

- Real Don Steele KTNQ-AM

- JR Hafer

- Piet Soer

- Why and Wherefore

- Rosko

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- She or He

- No Comparison

- The Old Train

- Jane Doe

- A Coffee Mug

- All Eyez on Me

- US Election 2016

- M Adam Roberts

- The Visitation

- A Woman

- Lessons in the Park

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Harmony

- There is a Light

- The Future