Fleetwood Mac

Jennifer Flaten

“Fleetwood Mac,” says Patrick Donavan, sometimes music critic for the Sydney “Morning Herald,” is a puzzle. “Mac” may be among the great, but lost, blues-bands. It may be a high point of soft pop music or Los Angeles excess. “Mac” may be the best, if not the greatest, pop band, ever.

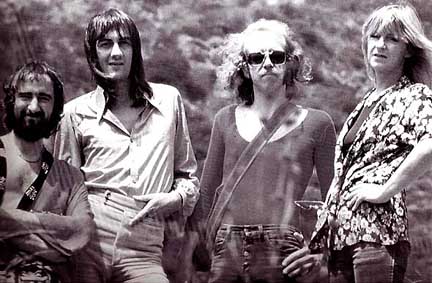

Mick Fleetwood, John McVie, Peter Green,

Jeremy Spencer and Danny Kirwan

As a blues band, “Mac” is the child of Peter Green, nee Greenbaum, a slick and imaginative, if affected, blues guitarist. After performing with several bands, London-born Green replaced Eric Clapton, in “John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers.” He hired on for three shows and stayed.

Mayall claimed Green was better than Clapton. This was heresy, in 1966; there was no mention of Jimmy Page. “The Supernatural,” a solo in D-minor ad-libbed by Green, was technically strong, if tiresome and dull. Mayall claimed “Supernatural” confirmed he was right about Green.

“Supernatural” showed Green could mesmerise himself, for long periods, without dispersing a mostly spacey audience. The instrumental appears on “A Hard Road," the first Bluesbreakers album with Green. “Supernatural” presages “Black Magic Woman,” also composed by Green and covered, in 1970, by “Santana.”

Urged by Green, Mayall replaced Aynsley Dunbar, a singularly talented drummer, with Mick Fleetwood. Though considered the top session drummer, Dunbar is likely most widely known for the four albums he recorded with “Journey,” in the 1970s. Still, Mayall hired Fleetwood, for rumoured reasons; at the time, John McVie played bass for Mayall.

Green left the “Bluesbreakers” on 15 June 1967. Mick Fleetwood joined Green after run-ins, with Mayall, about sobriety and performing. Jeremy Spencer played guitar in the new band formed by Green.

At first, John McVie declined to join the new group; Bob Brunning played bass until McVie changed his mind. Either liking the ring of Fleetwood “Mac” or hoping McVie would join, Green called his new band, “Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, featuring Jeremy Spencer.” McVie joined the new band in September 1967.

In a Hollywood movie moment, “Mac” signed a recording contract, with Blue Horizon, based solely on the reputation of Green. Their eponymously titled first album topped UK charts for a year. Two singles, “Black Magic Woman” and “Albatross,” also composed by Green, sold well, as did two more albums, “Mr Wonderful” and “Jam at Chess,” recorded at the Chess Records studios in Chicago, Illinois.

Fans in the UK took to “Mac,” but Americans didn’t. The band opened US tours by “Jethro Tull” and Joe Cocker, but sold few albums. “Tull” and Cocker weren’t as popular as “Mac,” in the UK.

“Mac” broke up, after release of its fourth album, “Then Play On.” In 2009, John McVie told the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) how Green binged on LSD, in 1970. The binge his changed Green and his music. “He wanted us to give our earnings to charity,” says McVie.

The last Green performance, as a full-time member of “Mac,” was 20 May 1970. The show ran overtime. Someone cut the power. Mick Fleetwood kept drumming until forced offstage.

One of the great, lost blues bands is a reach for “Mac.” A self-indulgent guitar player, striking a few good notes, makes for an above average band, at best. “Fleetwood Mac,” a good blues band in a time of too many blues bands, is not among the great, lost blues bands.

After Green, “Mac” morphed into a pop band. Danny Kirwan joined “Mac,” in 1968, as second guitarist. He and Jeremy Spencer easily filled the void left by Green, if only because the band drifted toward mainstream pop music. The first post-Green album for “Mac” was “Kiln House,” a giant step toward a softer, middle of the road sound, accessible to a much wider audience.

Christine Anne Perfect, now married to John McVie, was a session musician on “House.” She designed the album cover, too. Her first live show, with “Mac” and as Christie McVie, was in May 1970.

McVie nee Perfect had worked with “Chicken Shack,” an acceptable blues band, in the late 1960s. “Shack” had one hit, “I’d Rather Go Blind.” McVie won the “Melody Maker” best female vocalist award for 1969 and 1970.

During a tour stop, in February 1971, Jeremy Spencer went to buy a newspaper, but did not return. He joined a religious cult. Peter Green finished the tour, with “Mac.”

John McVie, Mick Fleetwood, Bob Welch and Christie McVie

Bob Welch, hired without much of an audition, replaced Spencer. Two new albums came quickly, “Future Games” and “Bare Trees"; both did well in the USA, but not in the UK. The blues version, of “Mac,” had little success in the USA, whereas the pop version did well.

“Bare Trees” included “Sentimental Lady,” written by Welch. Five years later, after leaving “Mac,” the song formed the bedrock of his solo career. Double dipping is good.

Danny Kirwan left “Mac” in 1972, alienated from the other members because of alcoholism and the severe stage fright it caused. The next few years were difficult. The line-up changed. A tour, in support of a weak album, “Penguin,” failed because of adultery and fraud. Band manager, Clifford Davis, formed a fake version of “Mac” and tried to tour it. Lawsuits followed.

“Mac” moved to Los Angeles. Promoter Bill Graham convinced Warner Brothers that Welch, Fleetwood and the McVies were “Fleetwood Mac.” They could record. Mick Fleetwood assumed management of the band.

The first album for the USA-based “Mac” released in September 1974. Called “Heroes Are Hard to Find,” it's mildly interesting. “Heroes” gave no hint of the internal strife that plagued “Mac.”

Welch quit “Mac,” after the “Heroes” tour. He claimed the band sapped his creativity. Still, Welch left the musical basis of a pop band, industry contacts and an atmosphere conducive for success. He passed away on 7 June 2012.

Mick Fleetwood, Stephanie Nicks, John McVie,

Christie McVie and Lindsay Buckingham

Scouting a replacement for Welch, Mick Fleetwood came across Lindsey Buckingham. Keith Olsen, an engineer at Sound City Studios, in Van Nuys, California, played Fleetwood a cut, “Frozen Love,” from an acceptable album by “Buckingham Nicks.” This was a want-to-be Los Angeles band, with a repertoire that included early versions of “Rhiannon,” “Sorcerer” and “Monday Morning.”

The members of “Mac” wanted Buckingham. His vocals were good. His guitar playing was often strong, in a pop music way, as were his composing skills. Buckingham wasn’t available without his musical and then life partner, Stephanie Nicks. “Mac” relented. Keith Olsen joined the band, too.

Buckingham, Nicks and Olsen combined for smooth, if saccharine, harmonies. Fleetwood and the McVies provided a bluesy edge and power. The latter buttressed the former. Now, the band had three able writers, Buckingham, Nicks and, most important, perhaps, Christie McVie.

Re-formed, “Mac” released a second self-titled album: how creative and confusing. Four hit singles, including “Say You Love Me” and “Rhiannon,” resulted. This pop album sold five million copies in the USA.

“Mac” was now a pop band. Any blues influence Mick Fleetwood or the McVies harboured drowned in the slushy pop of Buckingham and Nicks. The music of “Mac” became Mantovani for baby boomers.

Although she presented as distressed and gloomy, the media dubbed Stephanie Nicks the icon of “Mac.” She glided around the stage, trailing silk scarfs: “Like a bird in flight.” Mostly, Nicks seemed bewildered, apart from band and audience: “Woman, taken by the wind.” A blank slate is easy to fill.

Christie McVie became the pop music bedrock of “Mac,” despite her edgy blues origins. “Over My Head” anchored the second self-titled album and got the attention of radio in America. This song cleared the way for success.

Nicks wrote creepy, crawly, eerie lyrics, such as “Rhiannon” and the dysphoric, yet pop, “Dreams,” sung in the voice of a woman-child. McVie wrote memorable, uplifting lyrics, such as “Don’t Stop” and “You Make Loving Fun.” “Dreams” was the only number one single recording for “Mac,” in the USA, and, ultimately, did more for Nicks, as a solo, than for “Mac.”

In February 1977, “Rumors,” the second album for the rejigged pop version of “Mac,” entered American charts at number one. Four top-ten singles drove the album. “Rumors” stayed atop USA charts for 31 weeks, selling more than 40 million copies.

“Rumors” is a strong pop music studio album. As band members endured convulsive personal problems, the producers, Ken Calliat and Richard Dashut, created the album. They enabled remarkable harmonies from an otherwise dysfunctional bunch; mixing took several weeks.

Creating autobiographical works of art is most painful. Such work often rings clearest for the audience. This seems true for “Mac.”

Rumors” is ecstasy from agony. Much personal strife made recording the album difficult; the McVies split, as did Buckingham and Nicks. The wild success of “Rumors,” 36 million units sold, worldwide, lies with Calliat and Dashut.

“Go Your Own Way” is the most enduring song by “Mac.” It’s the only “Mac” song made the list of “500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll,” published by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The first line reflects the strife among the McVies: “Loving you isn’t the right thing to do.”

The sentiment is obvious in “Second Hand News”: “I know there’s nothing to say, someone has taken my place.” During an affair, Christine McVie finds renewal: “Sweet wonderful you, you make me happy with the things you do.” is the first line of “You Make Loving Fun.” Hope follows in “Don’t Stop”: “If you wake up and don’t want to smile … open your eyes and look at the day. You’ll see things in a different way.”

Nicks offers a dreary, pessimistic side of romance gone sour. In “Dreams,” she writes, “Now, here you go, again, you say you want your freedom.” Taking the tone of a nun to primary school students, she writes, “But listen carefully to the sound of your loneliness.”

“Dreams” in a way, is an ideal song for baby boomers. The lyrics are selfish, whiney and controlling. “Players only love when they are playing. Say, women, they will come and they will go. When the rain washes you clean, you will know.” Catholic women may start late, but they’re too likely to believe their current love is forever.

To follow “Rumors,” the band wanted a big album, a double set. “Tusk” released in 1979. Recording costs topped one million dollars.

“Tusk” lacked a unified sound. John McVie claimed it sounded as an album by three solo artists, Christine McVie, Stephanie Nicks and Lindsay Buckingham. Mick Fleetwood declared “Tusk” his favourite studio album by the band.

Buckingham, influenced by Punk and new wave music, worked a minimalist style best heard in “Tusk.” Nicks continued her dysphoric writing, typified by “Sara,” which fit “Rumors” better than it did “Tusk.” Christine McVie wrote pop hits, such as “Brown Eyes.”

“Tusk” sold well, more than four million units, worldwide, in the first year of release. It didn’t match sales of “Rumors.” Only “Thriller” sold more units than has “Rumors.”

Live albums confirm what a band can or cannot do. “Fleetwood Mac Live,” recorded during a worldwide tour in support of “Tusk,” is telling. The band is good, solid and invigorating, but not superb.

Two live albums from “Journey,” “Capture” and “Greatest Hits Live,” reveal a skillful, often intricate and always compelling pop band. “Journey” drummers, post Aynsley Dunbar, weren’t Mick Fleetwood. John McVie and Ross Valory are comparable bass players. Otherwise, “Journey,” live, is far better than Fleetwood Mac, live, as is REM, “Live in Athens.”

“Mirage,” released in 1982, offered “Mac” on a pop music high note. The album lack any hint of experimentation, on which “Tusk” thrived. “Gypsy,” a long, tedious song by Nicks, may be the most remembered cut from this album.

A solo album by Buckingham morphed into “Tango in the Night.” The fifth studio album from this version of “Mac,” “Tango” sold about six million units worldwide. The album had two pop hit singles written by Christine McVie, “Everywhere” and “Little Lies,” written with her husband, at the time, Eddy Quintela, a keyboardist.

Dissatisfied with how the rest of “Mac” treated him, Buckingham left the band before the tour in support of “Tango.” “Mac” replaced him with two high caliber musicians. The addition of Billy Burnette, son of music legend, Dorsey Burnette, and nephew of Johnny Burnette, boosted the vocals. Rick Vito, an accomplished guitar player, who worked extensively with high-profile acts, such as Bonnie Raitt and John Mayall.

“Mac” thus improved. Everyone was replaceable, which all realized and returned. Musicians come and they may go, but in the end, it’s all about the fame.

After “Tango, Mick Fleetwood compiled a box set of greatest hits by “Mac,” called, “25 Years – The Chain.” “Chain” is the only “Mac” song on which Fleetwood, Buckingham, Nicks and both McVies have writing credit. The four-CD box set received rave reviews.

Sales for later albums by “Mac” were limp. Of the “Rumors” version of “Mac,” only John McVie didn’t seek solo success. The solo career of Nicks overshadowed other band members. For unfathomable reasons, other than misery needs company, Nicks sold 100 million albums, on her own, and toured successfully.

In 1991, the “Rumors” version of “Mac” reformed, briefly. They re-recorded “Don’t Stop,” the Christie McVie song, for the Democratic presidential candidate, William Jefferson Clinton. Twenty years later, the song often introduces Clinton, at his appearances.

Longing for the good old days, Fleetwood talked Buckingham, Nicks and the McVies into reforming “Mac.” A live album, “The Dance,” released on the twentieth anniversary of the release of “Rumors.” A live performance video, of “The Dance,” premiered on MTV, in 1997, and regularly shows during PBS fund-raising drives.

“Dance,” the first album in fifteen years for “Mac,” was mostly greatest hits, although some unreleased tracks, such as “Bleed to Love Her,” were included. “Dance” debuted at number one on the “Billboard Magazine Hot 200.” The video version ends with “Tusk,” featuring the “University of Southern California Trojan Marching Band” and is likely the best live recording of “Mac.”

The renewal of the “Rumors” version of “Mac” was good for Peter Green, too. He had a comeback, of a sort, with “Splinter Group.” In 1998, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inducted “Mac” as well as Green, but for his part in “Santana.”

Lindsay Buckingham, Mick Fleetwood,

Stephanie Nicks and John McVie

Patrick Donavan, of the Sydney “Morning Herald,” posed three questions about “Fleetwood Mac.” Is the band among the great, lost blues-bands? Is the band a high point of soft pop music or Los Angeles excess? Is “Mac” the best, if not the greatest, pop band, ever?

Answering a question with a question, if Peter Green is a great, lost blues musician, the original “Mac” was a blues band. John Mayall claimed Green as a better blues guitarist than Eric Clapton. Carlos Santana recast “Black Magic Woman,” written by Green, in a Latin rhythm thereby making Green a star.

“Tango in the Night” is a high point in soft pop music. To a Midwest or east coast USA listener, “Tango” sounds vanilla. The success of the album depended on template pop songs, such as “Everywhere” and “Little Lies.”

“Mac” is Los Angeles excess, in 1970 lifestyle, not music. Drugs, infidelity and success paved the way. “Sweet Little Lies” is about an affair Christie McVie had with a roadie. The McVies divorced during the recording of “Rumors” and Nicks and Buckingham split, permanently.

“Rumors” is a pop album that got ridiculously lucky. “Dreams” and “Rhiannon” play with the gloom embraced by baby boomers, fascinated by misery. “You Make Loving Fun” captures the endless, youthful summers boomers can’t forget. “Go Your Own Way” nicely strokes the autonomy boomers believe they want and can find, but don’t.

Fortunate or high point albums do not make a band the best. Sold out tours and a live album are the tests for best. “Mac” had several sold-out, worldwide tours and two shots at a great live album.

“Fleetwood Mac Live,” in 1980, is good. “The Dance,” in 1997, is better. On-site recording technology improved from 1980 to 1997, but isn’t why “Dance” is better than the earlier live album.

Unlike most “Mac” albums, “Dance” seems driven, hard. You can hear their resolve, born of a give it your all for one last shot attitude, among the riffs. “Mac” wanted to win its last major stand.

“Dance,” mostly a greatest hits performance album and video, is the best “Mac.” The band is at the top of its game, evoking much sentimentality among aging fans. “Mac” is the endless Labour Day Weekend for baby boomers.

“Mac” plays on, tours sold out if with anticlimactic effect. The “Rolling Stones,” no matter age, are must see cultural icons. “Mac” is good bang for your buck: predictable and easy on aging ears.

The music of “Mac” and its template antics make listeners and audiences happy, as do old time movies. “The Coasters” continue to perform, more than fifty years after topping the charts with “Charlie Brown.” The top band in the middle 1960s, “Herman Hermits,” tours endlessly, as does Mark Lindsay, once lead singer of “Paul Revere and the Raiders.”

Contenders for top pop band, ever, must have a defining song. Most every band has a signature song; Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra ended each concert with “My Way.” A defining song has an effect beyond the artist.

“If You Leave Me Now” defines “Chicago” and generations of twenty-something lovers, now and forever. “If” is the second most played song on radio, ever. Such extensive airplay confirms the importance of the song beyond the band and time.

Defining songs happen. “All Right Now” defined the band, “Free,” as well as a style of rock music, but Andy Fraser and Paul Rodgers didn’t try to write a defining song. Success eludes the composer trying to write a defining song.

What “Mac” misses is a defining song. There’s no “Hotel California” for “Mac.” Many of its hits, “Rhiannon,” “Dreams” and “Silver Spring,” for example, link to Stephanie Nicks more than to the band; she usurped memories of “Mac.”

There’s no digging in the past to find the defining song. Words and music, artist, arranger, producer and engineer cohere in a perinatal spirit. This did not happen for “Mac,” as I t did for Rod Stewart, on “Maggie May,” and Marvin Gaye, on “What’s Going On.”

Digging around for a defining song leads to re-defining. “Don’t Stop Believing” now defines for “Journey.” In retrospect, “Every Time You Go Away” defines Daryl Hall, if not “Hall and Oates,” a long generation after release.

Looking back, there are many defining songs for “Mac,” but what you see in the rear view mirror doesn’t count. The rear view mirror reveals idiosyncratic choices. “‘You Can Go Your Own Way,’ defines ‘Fleetwood Mac,’ for me,” says Mary. “First time I heard it, on the radio, was right after Billy broke up with me.”

“Rumor,” “Tango,” “The Dance” or any “Mac” album doesn’t make “Mac” best pop band, ever. “Mac” is a great band, a top band, a memorable band; its music is the soft and smooth soundtrack for aging baby boomers. The title of best band, of any sort, eludes “Fleetwood Mac.”

Sources

Fleetwood: My Life and Adventure in Fleetwood Mac (1985)

John McVie - "Peter Green: Man of the World", BBC TV, 2009

Jennifer Flaten lives where the local delicacy is fried cheese, Wisconsin. She writes about family life, its amusing or not so amusing moments. "At least it's not another article on global warming," she says. Jennifer bakes a mean banana bread and admits an unusual attraction to balloon animals and cup cakes. Busy preparing for the zombie apocalypse, she stills finds time to write "As I See It," her witty, too often true column. "My urge to write," says Jennifer, "is driven by my love of cupcakes, with sprinkles on top. Who wouldn't write for cupcakes, with sprinkles," she wonders.

- A Tisket, a Tasket

- More Cupcakes

- Love is in the Air

- Different, but No Comparison

- Digital Revolution

- Census Time

- The Doorstop

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- A Big Wet Kiss

- Giant-this Largest-that

- The Eight Criteria

- Sjef Frenken

- A Fine How-dy Do

- Contact

- Espirit de Core

- Jennifer Flaten

- Carly Simon

- Clothspin Corpses

- Open Wide

- M Alan Roberts

- Fired Up

- I'm on Fire

- Please Shut Up

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Sundays at 5 pm

- Daphne

- Memorial Day

- Bob Stark

- Grey Cup 2013

- NHL Final 2013

- Boomerang

- Streeter Click

- Courtney Love Writes

- What is Journalism

- Gabe Abelson

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Castle Bonnie

- Still Missed

- The Babies

- Jane Doe

- All Eyez on Me

- A Coffee Mug

- The USA in 2017

- M Adam Roberts

- In the Subconscious

- The Great Lie

- Best Mom

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Monkey Business

- The Future

- Harmony