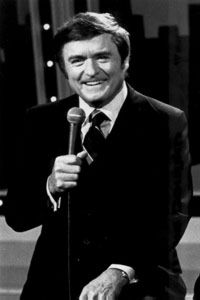

Burt Dubrow

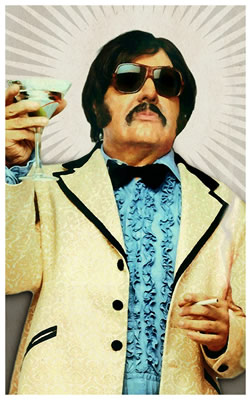

dr george pollard

Introduction

Dubrow is frank. A Game Show Network (GSN) executive asked him what show he’d produce, if he had no limits. Dubrow said a gay version of “The View.”

From this remark, a clever revival of a 1950s game show arose. The show, “I’ve Got a Secret,” aired on GSN in 2006. The artful move was finding a vibrant, all-gay panel,

The panellists had a matchless chemistry. This is the secret to any game show, says Dubrow, chemistry. Viewers want to watch good-natured teasing.

Burt Dubrow succeeds with ease. This is a rare gift. He suggests his winning creation, “The Jerry Springer Show,” popped up on a regular a day at the office.

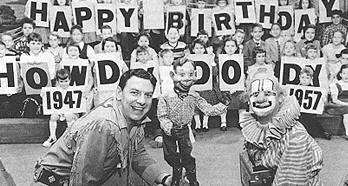

“Howdy Doody,” the puppet, which enthralled children, is the Dubrow muse. “Howdy” and his adult friend, “Buffalo Bob” Smith, were fad and fashion in the 1950s. Their images appeared on lunch buckets and children wore check shirts, as did “Howdy.” This is a puppet treated with the awe accorded a religious icon.

When talking about “Howdy Doody,” a different Dubrow awakens. His pace slows. His voice softens. He recalls “Howdy” nuance and minutia at lightning speed. Talk of puppets takes Dubrow to a higher, simpler, more innocent world.

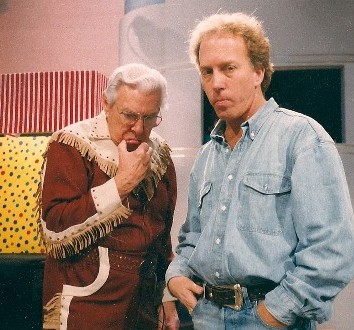

A live show, featuring a “Howdy” episode and “Buffalo Bob” Smith, toured college campuses in the 1970s. Its success was remarkable. Dubrow left college to work the tour as the emcee and road manager; who wouldn't.

Success, for Dubrow, lies in an odd unison of muse and passion, “Howdy Doody” meets “Jerry Springer.” Creativity is joining unalike parts in a flourishing union. The question is how the road winds from “Howdy” to Springer.

Dubrow is unapologetic. On Springer, he admits, exploiting guests to keep the show going, but we revealed a hidden part of America, too. Americans need to know about the lives of the guests on Springer.

Dubrow imprints his style. He’s the force propelling his television shows. Auteur, an adjective most often applied to filmmakers, legitimately fits Burt Dubrow and to a tee.

Still, he bangs his own drum lightly. Dubrow delights in the excellence of others. The auteur takes pride in his art.

The success, of “I’ve Got a Secret,” he says, lies with the panellists: they found a unique chemistry. Sally Jessy Raphael did “Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood” for adults, knowingly and superbly. Springer, remaining calm, eases the pulse of an expectant, loudly complaining and, too often, violent America.

Dubrow knows, too, the golden past of American television. As he lunges into the future, he’s eager to reflect on the past, a fact perhaps shrouding his larger purpose: our future loses much if we don’t know or learn from the past. Dubrow thus echoes Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, among others.

In this interview, exclusive to Grub Street, Dubrow, as pop culture auteur, cuts a wide swath. His message confirms age-old advice: follow your dream and do what you love, the rest will take care of itself. Thus, it does for Burt Dubrow.

There is always a moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in ....

Grahm Greene,

in "The Power and the Glory"

Grub Street (GS) "Howdy Doody,” an influential television show from the 1950s, unexpectedly opened many doors for you.

Burt Dubrow (BD) “Howdy” was first for me. I mean “Howdy” was it. I don't know why, but this show was a huge deal for me, when I was a child and today.

There was a live feeling to “Howdy Doody.” How can string puppets give anyone the sense of honestly live television? Well, “Howdy” did; that show remains important to me.

"Howdy Doody"; "Photo Doody" with "Howdy"; "Howdy" with Buffalo Bob"

Puppets fascinate me, even as an adult, if for different reasons than when I was a child. Think about it. “Punch and Judy,” in one form or another, were popular for hundreds of years. Puppets have universal appeal, to children, to adults and across time.

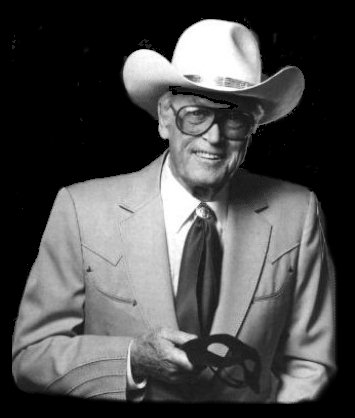

Bob Smith was the consummate host for a television show aimed at children. As children, we like big animals that we’re safe from, dinosaurs, for example. Smith played much the same way on the “Howdy Doody” show: a big, genial man, protective of “Howdy” and all children.

There was a raw quality to the show, too, which I liked. It was a live-to-air, daily television, in the 1950s. Make a mistake and everyone knows. The show blazed the path for television and for television aimed at children.

There were many mistakes. This has an appeal, too. Risky, but natural, whereas, today, multiple retakes give the impression the stars get it right the first time, which isn’t true.

GS What was the premise of the “Howdy Doody” show?

BD It was a television show for children, supposedly hosted by a child, a child puppet. There were contests, stories, a short sitcom and guests with special skills. The show used whatever adults, the creators, writers and producers, thought kids might enjoy. Strong, positive relations between adult characters, such as “Buffalo Bob” Smith, but children, represented by “Howdy,” were most important.

The influence of “Howdy” is subtly evident in the work of movie producers, especially, Steven Spielberg and John Hughes. Their movies, the ones with children as heroes, such as “ET” or “Home Alone,” reflect the relations between “Howdy” and “Buffalo Bob.” The children achieve much when adults are supportive and allow children the chance to succeed.

“Howdy Doody” began as a one-time Christmas 1947 television show for children. Bob Smith created a show, from scratch, that aired, with no sponsor, at 5 pm on 27 December 1947. NBC paid Smith $75, for the show; he gave writer Eddie Kean $25.

There were only 20,000 television-owning homes, in New York City, the day “Puppet Playhouse” aired. A 25-inch snowfall kept every child inside that day. All the kids, in all the apartment buildings, in New York City, circled the one or two television sets in the building to watch “Puppet Playhouse.”

Reaction to the show was overwhelming. NBC wanted more episodes of “Puppet Playhouse.” Early in January 1948, a show began airing on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, at 5 pm, with a circus theme.

For that first season, Smith dressed as a lion tamer, of sorts. Eddie Kean wrote every single episode. Kean created all the eventual “Howdy Doody” characters.

The show was walking a new path. There was no model to copy, no map. It was raw, every episode novel and risky.

After the short-lived circus theme, of the first episodes, the “Howdy Doody Show” was generic. In middle 1950s, the clubhouse theme took over. The show cut back to thirty minutes, in 1948, running at 5:30 pm, Monday to Friday. Bob Smith became “Buffalo Bob,” a natural character name, as he was from Buffalo, New York. Eddie Kean continued to write. The show was much more polished than the previous year.

The producers added a small audience, of about forty lucky children, to the show. The “Peanut Gallery,” the nickname of the live audience, is a term that remains part of American pop culture to this day. I was a member of the “Peanut Gallery,” a visitor to “Doodyville,” many times.

GS As a child, you found a way to meet and know Robert Emil Schmidt, I mean, Bob Smith.

BD He owned a store, a package store, in New Rochelle, where I grew up. When I discovered this fact, I took the cross-town bus to visit him, in the store, several times a week. This is how I came to know Bob Smith and sit in the “Peanut Gallery,” often.

Often, I later learned, Smith would see me get off the bus, down the street from his store. He’d go into the back of store so I wouldn’t bug him. His brother, Vic, would tell me he was off rehearsing with “Howdy,” he didn’t know where.

GS The show moved from daily to weekly, for the last few years of its run.

BD In June 1956, “Howdy Doody” moved to 10 am, Saturday, on NBC. I remember this version, well. My collection includes copies of all the shows kinescoped; I’ve seen all the available shows.

GS Where did they get the name, “Howdy Doody”?

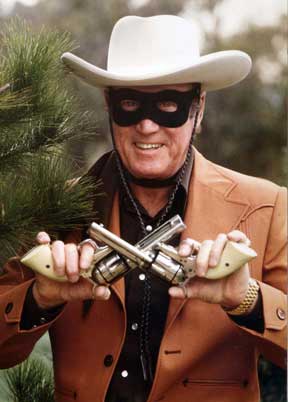

BD It’s simply a play on a common line spoken by cowpokes in western movies, of the time. Bob Smith was doing a radio show called “The Triple B Ranch.” Asked if he could do any characters, Smith offered Elmer.

Every time Elmer appeared, he’d say “Howdy Doody,” as he would when he left. Developing the one-off Christmas time television show for NBC, Smith decided to name the main character, “Howdy Doody.” The full version, of the line, is in the theme song, of the show, sung by Bob Smith.

The “Howdy Doody” theme song became a best-selling hit record. It was the television theme to top the charts. Many other themes, such as “Hawaii 5-0,” followed “Howdy” to the top of the charts.

GS I suspect at least one main character, from the show, wouldn’t survive today.

BD If you’re not politically correct, the show is great. There’s a Native American character, “Chief Thunderthud,” played by Bill LeCornec; he looked the part of a seasoned Shakespearean actor. LeCornec also voiced the character, “Dilly Dally.”

"Buffalo Bob," "Howdy" and "Clarabell"

There was a clown, “Clarabell.” He got his message across by honking horns and squirting seltzer. The only time Clarabell spoke was on the final show, he said, “Goodbye, kids.”

Bob Keeshan, later “Captain Kangaroo,” on CBS, was the first “Clarabell.” He left the show after the Christmas Eve Massacre, of 1952. Fed up with a salary dispute, Smith and the producer, Roger Muir, fired everybody in the cast that night.

It didn’t take long for Smith and Muir to realize they couldn’t produce the show, successfully, without the main cast members. There was a general rehiring, but no actor had a contract. Keeshan most actively looked for other work and found a new job at CBS.

In early 1953, Bobby Nicholson, a friend of Smith, from Buffalo, replaced Keeshan. Nicholson was a musician. If Smith had his way, everybody on the show would be a musician.

After a few years, Nicholson got bored doing the silent Clarabell. In the middle 1950s, he left the show. Nicholson went on to do voice work for cartoon characters and on commercials.

Then Lew Anderson, a widely known jazz musician, took over the “Clarabell” role about 1956. He was one of my dearest friends. I spoke at his funeral, in May 2006.

I knew the actors who portrayed each character, on the “Howdy Doody Show.” I made it my business to get to know each one of them. I was more than a fan.

GS “Howdy Doody,” I think, was the first network television shows in full colour.

BD Yes, in 1956, it was the first daily show in full colour. I remember seeing the colour version, of the show, at the home of a friend. I thought I’d pass out, seeing “Howdy Doody” in full colour.

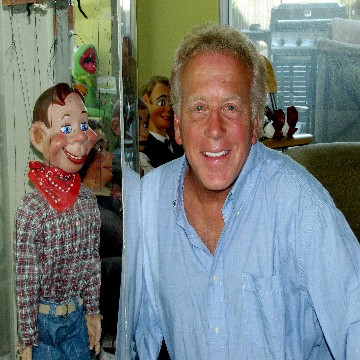

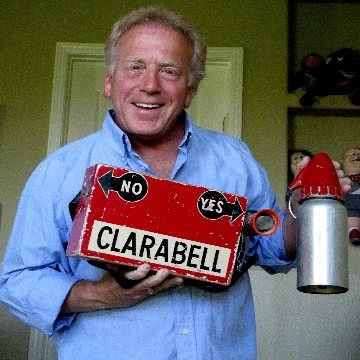

To this day, I’m obsessed with the show. I own costumes from the show. I have some of the puppets, including a “Howdy.” Velma Dawson, one of the original “Howdy” puppet builders, gave me the one I have; it’s an original.

GS Who would know Velma Dawson, today?

BD Nobody, even during the run of the show, few knew of Dawson. For some reason, she was seldom, if ever, mentioned. In the 1970s, I decided to find her and about her.

She was wonderful. In 1975, NBC decided to honour “Howdy,” with a prime time special. I put the show together, making sure Velma Dawson was a part the show and she gave me a “Howdy” head.

GS You're kidding. You have more than a “Photo Howdy” or “Stand in Howdy.” You have originals, not knock-offs made after the show ended.

BD I have the moulds. I also have the last “Photo Doody,” which Smith used in the last fifteen years or so of his life. That “Photo Doody” is sitting downstairs, right now.

GS “Photo Howdy” didn't have as many strings, as I recall.

BD No, there’s only one string for his mouth. Smith used “Photo Howdy” almost like a ventriloquist figure. It sat on his lap for photographs. This avoided hiring a puppeteer for photo shoots or personal appearances.

If “Howdy” did personal appearances that meant the puppeteers had to come along, too. This was expensive, but more important it would “kill” the illusion. “Howdy” was 27.5 inches tall and needed puppeteers to bring him to life.

On television, “Howdy” worked on a raised platform. He was at eye-level, with Smith and other adult characters. Viewers got a sense he was tall.

“Howdy,” in any form, did few live public appearances, while the show aired. When Smith toured, after the show went off the air, the size of “Howdy” didn’t make much difference. Many in the audience had not seen the show, live, on television; most everyone came to witness pop culture.

GS How many “Howdy Doody” shows aired?

BD From 1947 to 1960, 2543 “Howdy Doody” shows aired. It was the first television show to pass two thousand original episodes. There were sixty-minute shows, three days a week, for a few months. Then five 30-minute shows a week and, for the last 5 seasons, one 30-minute show a week.

Until 1955, each show was live; thereafter each show taped. Each show relied mostly on new material, mostly written by Eddie Kean. Each show called for unimaginable creativity and skill, rarely seen today.

GS Interesting how times change, NBC recently cancelled “Law and Order,” the mother ship show. It had a 20-year run, but fewer than 450 original shows. “Gunsmoke” also aired for twenty years, on CBS, with fewer than 500 shows.

BD Yes, “Howdy Doody” aired for 13 years and 2543 episodes.

"Howdy" and Dubrow; with answer board and seltzer bottle used by "Clarabell"; with "Buffalo Bob," on set of "Sally Jessy Raphael," about 1985.

GS What do you think an original “Howdy” would sell for, today, at auction?

BD I know the original “Photo Doody” went for $130,000, at auction, not long ago. The original “Howdy,” used only for the television show, lives in the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Long after the show and the touring ended, Bob Smith wanted to sell his “Howdys,” which set off a firestorm of legal action, much of it unexpected. The Smith set was worth a fortune; Michael Jackson wanted to buy one or the whole set. The problem was Smith didn’t own “Howdy,” though he used them.

GS Who owned “Howdy”?

BD For a long while, ownership was a much asked and little answered question. NBC thought it owned “Howdy Doody.” The heirs of puppeteers, Rufus and Margo Rose, thought they owned the puppets.

When the show ended, NBC gave Roger Muir the on-air “Howdy,” in use at that time. He produced the show through its entire run. Muir sold that “Howdy” at auction and that was that.

In 1960, when the show ended, Rufus Rose was head puppeteer and his wife, Margo, his first assistant. Rufus and Margo were famous, in their own right. They worked as the Rufus Rose Marionettes.

At the time, NBC didn’t know what to do, with “Howdy” and the other puppets. These were props to the network. The puppets were not different from scenery.

NBC let Rose take “custody” of “Howdy” and friends, when the show went off the air. Rose kept the puppets in his workshop, all but the original, on-air “Howdy.” The original “Howdy” had a special place in the Rose home.

One day, the Rose workshop burns down, probably in the late 1960s. A newspaper gets wind of the fire and headlines, “Howdy Doody Burns in Fire.” Bob Smith told me his mother received condolence notes; some people couldn’t disconnect Smith from “Howdy,” let alone television from everyday life.

The story of the fire played in media across America and NBC goes out of control. Its executives hit the ceiling. “We own the puppets,” they claim. “Rose only had custody.”

NBC sues Rose, but doesn’t do its homework. When Rose is about to testify, he brings “Howdy” along. Rose is sitting in the witness box, with “Howdy” on his knee. NBC claimed “Howdy” had burned, but there he was, in the courtroom.

GS Shades of the movie, “Miracle on 34th Street.”

BD Yes and Rose then sued NBC. He won. As part of the settlement, NBC gave “Howdy” and his puppet pals to Rose. After Rufus and Margo Rose passed away, their children sold the puppets at auction.

GS These icons of pop culture should be in the Smithsonian Institute.

BD There’s a “Howdy” in the Smithsonian, one of the doubles. Everyone says what you say, but the problem, with the Smithsonian, is when you give it something, it can do whatever it wants with your gift. The basements, of the Smithsonian, three stories below ground, are full of treasures.

GS How did “Howdy” find his way to the Detroit Institute of Art?

BD It’s a long, involved story, but here’s the short version. Originally, Smith and Roger Muir owned rights to the show, characters and puppets. In the early 1950s, I think, they sold everything to NBC, with Smith keeping only the “Buffalo Bob” character.

By the 1970s, after the ownership lawsuits, Rufus and Margo Rose, the puppeteers on the “Howdy” show, owned all the puppets. This included the puppet Smith used. When Smith was touring “A ‘Howdy Doody’ Revival,” in the early 1970s, he needed permission to use a puppet, occasionally, specifically, “Photo Doody.”

Smith asked NBC, which owned the rights to “Howdy,” if he could use the puppet. They agreed. Smith then asked Rose, who owned the puppets, for the original “Howdy.” Rose offered Smith use of the original “Howdy,” adding that when Smith finished using the original “Howdy,” he must give it to the Detroit Institute of Art.

After Rufus and Margo Rose passed away, their son, Chris, wanted to sell the puppets. He talked to Smith. They agreed to sell the “Howdy” and split the money.

Smith forgot about the “after you’re finished” part of his deal with Rufus. The Detroit Institute of Art, which Rufus copied on his letter to Smith, did not forget about this part of the deal. The Institute wanted its “Howdy.” Smith declined.

All sides hired lawyers. Chris Rose asked, “How do we know this ‘Howdy’ is the original?” Since 1948, replacing puppets and puppet parts was a steady industry. How do we confirm if this is the original “Howdy Doody” or not?

No one knew, but this was the question. Everybody must find out. Both sides spend time and money to study the issue. Meanwhile, a judge stores “Howdy” in a drawer, in a bank vault.

GS How indignant is that?

BD Rhoda Mann, who ran “Howdy” from 1948 to 1953, says it’s not the original “Howdy.” Velma Dawson, who made the early puppet, used on the show, waffles, but decides this is the original “Howdy.” I, too, confirm it as the original; I’d seen it, up close and personal, on a regular basis, since I was a child.

The lawsuit drags on for years. Bob Smith passes away before the case resolves. Eventually, the Detroit Institute of Art wins and takes possession of “Howdy”; the Rose heirs auction the other puppets.

Jermaine Talyor, Bill Dwyer, Frank Decardo, Suzanne Westhoefner and Billy Bean on the set of "I've Got a Secret"

GS In 2006, you produced, with Jean Wigman, a clever revival of a classic 1950s and 1960s game show, "I've Got a Secret." How did that come about?

BD Well, I’m a fan of television. I lived and breathed television as long as I can remember. I love older television, such as “Secret,” “Howdy Doody” and so on.

The older shows had no model, as they do today. The producers, Gil Fates on “Secret,” flew by the seat of their pants; it was an exciting time. In the 1950s, television producers invented as they went along.

GS It was an adventure, in the early days.

BD The thrill of the new frontier, in a sense, is why I love older television. Reviving “Secret” was a way for me to revive a television format, the panel show. I believe the panel format still has a place on television.

GS How did you present the idea, for a revival of “I’ve Got a Secret,” to the Game Show Network (GSN)?

BD In 2005, I think, we, Jean Wigman and I, broached Ian Valentine, at GSN. He headed programming and Rich Cronin ran the network, at the time. Originally, we wanted to tape the show in black-and-white.

GS I can’t imagine that GSN, of all networks, would take such a creative, risky leap as using black-and-white.

BD About 2005 or so, George Clooney produced, “Good Night and Good Luck.” The movie was about Edward R. Murrow, CBS News and McCarthyism in the 1950s. Clooney wisely filmed in black-and-white to capture the era and maybe the issue. I hoped to build on that idea.

We wanted to do “Secret” in a way that reminded viewers of the 1950s or 1960s, before colour television was everywhere. We wanted the panel, even the contestants, to dress in 1950s or 1960s clothes. This is the idea we pitched to Valentine.

GS Rarely do I think going backward is either creative or innovative, but your pitch for “I’ve Got a Secret” was imaginative.

BD During my pitch, Valentine changed the subject, asking if there’s a show we wanted to do, but couldn’t find a way to do. Right away, without pause, I say, sure, an all-gay version of “The View.”

GS What can I say that won’t get me sued?

BD We laughed about that idea. Yet, here were the roots of the "I've Got a Secret" revival. It revolved around an all-gay panel.

GS Why an all-gay panel?

BD The simple, the blunt, answer is we couldn’t sell “Secret,” if what we wanted to do was revive the old show, in the same format. There was no way Valentine would buy a retread. He needed a spin.

We, Jean Wigman and I, needed a hook. After my joke about “The View,” Valentine, Wigman and I wondered about an all-gay panel for “Secret.” Given the times, the all-gay panel idea might work, we thought.

Two facts, I think, drove our thinking on this idea. One, every game show, new or old, needs a hook. In the 1950s, each contestant had a secret the panel tried to guess, but this wasn’t enough for a 2006 version of “Secret.”

Two, television game shows live or die on the chemistry of the panel. “Hollywood Squares” used a nine-person panel and tried to script the chemistry. “Secret” originally used two men and two women, but only after changing two panellists, years into its run, did all four panellists gel.

We thought, on an all-gay panel, the members would sense themselves part of a group before they started. Remember, we developed a panel of four people who had not met. Whatever brought them together, other than the show, provided a stronger sense of camaraderie, giving us a head start.

I think we were right, on this one.

GS Yes, no question about it, your revival of “Secret” was exceptional.

BD An all-gay panel was a great idea, but, as we learned, hard to pull off. Where do we find the right panellists? How do we pick panellists who can develop chemistry, never mind the right chemistry?

It took us about eight months to cast the panel. We had casting many calls and talked with potential panellists. It was difficult.

We might have ten women and men in for a casting call. We’d run through the show, mixing and matching potential panellists, trying to find the right mix. One day, three men and one woman clicked, for us, and they formed the panel we used to shoot the 45 shows in 2006.

Jermaine Talyor, Suzanne Westhoefner, Frank Decardo and Billy Bean

GS What were you looking for in potential panellists?

BD I’m a huge fan of “Match Game,” especially the 1973 to 1982 version. This is likely my favourite television game show, ever. The chemistry, which developed between Charles Nelson Riley and Brett Somers, is unbeatable.

What we, Wigman and I, were after was an updated version of the Riley and Somers chemistry. Our hard work, choosing panellists, paid off. Suzanne Westenhoefer (above left) and Frank DeCaro (above, second from let) were brilliant. They had a different chemistry than we expected, but much better than ever hoped.

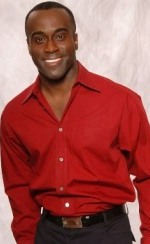

GS You caught lightening in a bottle, thinking it might not strike twice. Billy Bean (above right), a former baseball player, was on the lecture tour and readily available. How did you find Jermaine Taylor?

BD Jermaine Taylor (above, second from right) was in New York City. He sent us a videotape. As soon as I watched his tape, he had the job.

Harking back to “Match Game,” Taylor was much like the late Julius “Nipsey” Russell. Dick Clark called Russell the “poet laureate of television.” As usual, Clark was right.

In his frequent appearances, on “Match Game,” as a guest panelist, Russell would recite a short poem and, more often than not, reveal an answer that matched the contestant. As a stand-up comedian, Russell was among the sharpest. In the 1960s, Russell told a story about, “a Black man who goes into a restaurant and is refused service. But I’m the UN delegate from Ghana,’ he says. The waiter says, ‘Well, you ain’t Ghana eat here.’”

The wit, of Taylor, as Russell, is razor-sharp. Taylor fooled around, but when it came his turn to question the contestant, he often guessed the secret. He was also much like Henry Morgan, the satirist and panellist on the original “Secret”; their waters ran deep.

GS Yes, Morgan seemed more reserved than did Russell, but they shared a rare wit and satirical reflex. Taylor was always on the mark.

BD William Daro “Billy” Bean was the hunk, on the show. He was a top baseball player, with the Detroit “Tigers,” Los Angeles “Dodgers” and San Diego “Padres,” hitting a career .226. In 1999, he confirmed he’s gay, only the second major league baseball player to do so.

GS Bean seemed, recalling “Match Game,” the Richard Dawson of “Secret.”

BD Well, yes, but Bean had much less attitude. Many people thought Bean too good-looking, too hunky, to add much substance to the show. Bean did a great job, as did all the panellists.

Viewers quickly learned Bean asked the right questions. If he didn’t guess the secret, Taylor, who was up after him, often did. Their chemistry was good, if different from Westenhoefer and DeCaro.

There was an exceptional, if unexpected, balance in Westenhoefer and DeCaro, Taylor and Bean. As I said, the balance was not what we aimed for, but better. “Secret” reaped the benefits of serendipity.

GS You didn’t do much production, nothing fancy, on “Secret.”

BD No, we relied on the panel. It was a wise decision. Our production, we thought, was unusual contestants.

Once, with the panel blindfolded, the contestant was the mother of panellist Jermaine Taylor. The extent of positive reaction, to this stunt, caught us off guard. There wasn’t a dry eye in the studio.

“Little Kiss,” a tribute band comprised of dwarfs, was also a contestant. The band performed, live, at the end of the show. Viewer reaction, to “Little Kiss,” was great.

GS The last contestant, on “Secret,” was Martha Wash.

BD Yes, she had been part of the duo, “Two Tons O’ Fun,” with Izora Rhodes. After their hit, “It’s Raining Men,” they changed their name to “The Weather Girls.” Rhodes passed away, in 2004; Wash continued as a solo.

Wash is a major star of Dance and Club Music. To end the production run, of “I’ve Got a Secret,” on GSN, with her, singing, “It’s Raining Men,” was perfect. Viewers, who would never think of going to a dance club, loved her; the reaction surprised us. She ended our run, with a subtle message.

GS I don’t recall GSN promoting “Secret” as gay-oriented or admitting panel was all-gay.

BD When we started, GSN intended to promote the gay angle. Before we went-to-air, GSN decided to promote the show in a different way. It decided it didn’t want to go down that road.

It’s interesting, I think, how many viewers never recognized the gay angle. Some sensed the gay angle, but the talent, of the panel, overrode any concerns. If the panel were all men, then, maybe, some viewers would have noticed, but Suzanne Westenhoefer confused the mix.

What threw everybody, I swear, was putting Westenhoefer in there. Somehow, for some reason, she deflected the gay issue. I don't know why no one ever thought the word, lesbian.

In the middle of editing the pilot, I asked the editor if he found anything different about “Secret.” He said no, only it was especially funny. Then I told him about the all-gay panel and he said, “No!”

As well, we taped “Secret” much the way it ran in the 1950s. Mostly, the show ran live to tape, with some post-show editing for time and such. If someone flubbed or knocked over a glass of water, the tape rolled; viewers usually saw exactly what went on.

GS Watching “Secret,” on GSN, it seemed everyone got along and most everything went right.

BD It was a love fest. “Secret” was one of the happiest times of our lives. I especially enjoyed working with Jean Wigman. There was never an argument.

There was never a problem, on “Secret.” We loved one another. We loved the cast.

Frank DeCaro discovered a new side of himself, on the show. He became a little like Charles Nelson Riley. He wore funny clothes and flowers on his lapel.

I hadn't thought about “Secret” for a long-time. I’m thinking about it as we talk. It was wonderful.

When the mother of panellist Jermaine Taylor appeared, it was our defining moment. Our goal was for viewers to get to know the panellists as people; viewer reaction to his mother and his response were over the top. We knew, then, the show was working and we had captured the spirit of the original “Secret” and other shows like it.

Personality drives television game shows. If the panel develops chemistry, viewers love it and reward with loyalty. The show developed a strong chemistry, among the personalities, and with the audience.

GS Why do you think GSN didn't renew it?

BD Money, Secret,” though we didn’t do much production, was expensive to produce. There were four panellists; the perfect host, Bill Dwyer, studio and crew.

We had three secrets on each show. At first, we hoped to get contestants locally, from Los Angeles, but that didn’t pan out. We flew contestants to Los Angeles, putting them up in a hotel and shuttling them around. A contestant that stumped the panel got a thousand-dollar prize plus a fancy dinner in Beverly Hills.

GS Yes, I heard about dinner in Beverly Hills. Someone told me it was dinner in Beverly Hills, all right, but at McDonalds.

BD Production costs were unquestionably expensive for each show. This is much money for GSN. “Secret” was an expensive show, but it worked.

GS Why didn’t one of the big four networks, CBS, NBC, ABC or Fox, pick up “Secret”?

BD We didn’t pitch any of the big four: CGBS, ABC, NBC and Fox. Each would likely find “Secret” too slow. On a panel show, each panellist gets a turn, one, two, three and four. Hearing from each panellist doesn’t work, for the four major networks, given the pace of television today.

The pace of television mimics the pace of life. Life isast, today, frantic and frenetic. Viewers no longer know how to sit, patiently, through four panellists. I wish it would work, but it’s unlikely.

Charles Nelson Reilly, Brett Somers, host Gene Reyburn and Richard Dawson, on the set of "Match Game"

GS You mentioned Brett Somers and Charles Nelson Reilly, from “Match Game,” a moment ago. Can we talk a bit about “Match Game,” the long-running television game show? I know you weren’t part of the show, but I’m curious about your insights. First, let’s get the basic idea of the show.

BD As with “I’ve Got a Secret,” the basic idea was to find a way for the celebrities to develop a chemistry that would promote funny interplay. In the 1970s, Brett Somers and Charles Nelson Reilly developed a singular chemistry that helped drive “Match Game” to number one. You must see the verbal fencing, of Somers and Reilly, to understand, fully, its appeal and to understand it.

The secret, with Somers and Reilly, was everyone knew they were kidding. The verbal jabs were all in fun. If the audience thought, for a moment, that the barbs were real, the chemistry left and the show was gone.

The idea behind “Match Game” involved two contestants filling in the blank in a phrase. Host Gene Rayburn read a phrase, “Wow! Did you see the [blank] on that young woman?” During a 30-second pause, members of the celebrity panel wrote an answer to fill the blank, while Rayburn acted the fool or promoted a project that involved a guest.

From 1973 through 1979, a wide variety of celebrity-guest panellists cycled through “Match Game.” Each show featured three permanent panellists, Brett Somers, Charles Nelson Reilly and Richard Dawson as well as three guest panellists, such as Elain Joyce or McLean Stevenson, an up-and-coming starlet or someone trying to restart their career.

It seems the producers picked guest panellists for their flatness or looks. The guests stayed for a week, five shows, supporting and egging on the interplay among the permanent panellists. The regulars made the show a success; the guests were window dressing.

GS Same reason Merv Griffin picked Arthur Treacher as his sidekick and David Letterman uses his bandleader, Paul Schaffer.

BD Yes, when the panellists finished writing a word or phrase to the fill in the blank, Rayburn asked the contestant for his or her answer. He rewarded the best contestant answers, such as bum, boobs or a double-entendre, with much flourish and attention. Lesser contestant answers, such as shoes, earned groans from the live audience and little attention from Rayburn.

GS Among contestants there was much effort to please papa Gene.

BD Rayburn then asked each panellist to reveal his or her answer, usually with much fanfare. The game awarded a point for each celebrity answer that matched the answer offered by the contestant. The contestant who won the most points, in two-of-three rounds, played one more round, a super match, with a celebrity of their choice, for up to $5000 dollars.

GS Dull as dishwater on paper.

BD Right, it was the chemistry between Somers and Reilly, who were constantly on each other for poor answers or bad hair. “That’s not a dress,” Reilly once said of the wardrobe choice by Somers, “it’s my kitchen curtains.” Somers usually targeted various wigs worn by Reilly.

The presence of Richard Dawson completed the picture. He matched contestant answers more often than did any other panellists or it seemed that way. Dawson won the big money the at most often for contestants, in the special round, at the end of the game, or so it seemed.

Dawson was popular for successfully playing the game and his humour, which was personal. The interplay of Somers and Reilly lightened the show; their humour was inter-dependant. Only “What’s My Line,” in the 1950s and 1960s, topped the Somers and Reilly repartee.

When we revived “I’ve Got a Secret,” we looked to “Match Game” for inspiration. We worked on chemistry among the panellists. The interplay was most important. Picking and presenting the secrets was secondary. If the panellists didn’t click, there was no show.

GS Somehow, Rayburn engineered this potential run-away train.

BD Rayburn enthralled me, how he controlled the panellists. I was in television, at the time, working WLS-TV, in Chicago, or later on the “Mike Douglas Show.” I knew how hard it was to preserve control. Rayburn was singular.

After the second show taped, panellists and crew took a lunch break, before returning to tape three more shows that day. Lunch, of course, was on CBS and a cocktail or two was not out of line. After lunch, the teasing and friendly taunting, among panellists, rose to a new level.

Yet, Rayburn managed the mayhem, with �lan. Doing so, he made “Match Game” his show. Rayburn succeeded, despite working with panellists who were better known and more popular than was he, bigger than life as far as “Match Game” went.

GS Somers and Reilly were far more animated than was Rayburn.

BD Rayburn, given his solid performance as a quasi-permissive host, owned the show. I loved the idea nobody told the panellists what to do or not do. If the show didn't go right, Rayburn found a way to manage it. He had an exceptional ability and the talent to make “Match Game” work, well.

GS You produced a pilot with Rayburn.

BD Rayburn lived on Cape Cod. Toward the end of the “Match Game” run, he was tiring. Commuting to Los Angeles from Boston every two weeks and filming 10 shows over two days was difficult. When “Match Game” ended, in 1982, he thought he’d do a Boston-based show and commute only an hour from his home.

I did a pilot for a local Boston-based show, called “Helluva Town.” Rayburn was the host. He once did a television show, called “Helluva Town,” in New York City; in the 1950s, I think.

GS You own the microphone Gene Rayburn used on the CBS daytime version of “Match Game,” I read.

BD Yes, Rayburn gave it to me. As I said, television was almost the centre of my life as child. Microphones were a close second on my list of interests. No less than a camera, the microphone made television possible.

I used go to the Heath Kit store, which was much the same as Radio Shack, today; maybe more crammed with gadgets and other products. The microphones mesmerized me. To this day, microphones fascinate me. I collect microphones as well as “Howdy Doody” memorabilia.

As we filmed the pilot, for “Helluva Town,” I came to know Rayburn, well. He invited me to his home, on Cape Cod. We became good friends and he gave me the “Match Game” microphone, a Sony ECM-51, with the windscreen missing.

GS What do you know of his background?

BD He was a talented man, a broadcaster, in the traditional style. He was from Chicago; his birth name was Eugene Rubessa. I heard somewhere one parent was from Buda and other Pest, making him a rare, yet true, Budapestian.

Rayburn worked in radio after the Second World War. He co-hosted top-rated morning shows on WNEW-AM, in New York City: “Anything Goes,” with Jack Lescoulie, and “Rayburn and Finch,” with Dee Finch. He was the announcer on the “Tonight Show,” when Steve Allen was the host. Rayburn was also an actor, replacing Dick van Dyke, in “Bye, Bye Birdie,” on Broadway, in 1957.

He easily segued into television, in the early 1960s. Few game show hosts take hold of a show as strongly as did Rayburn. “Match Game” was his show, from day one.

GS Is there, today, a game show host you think fits in this category, taking hold of a show, as did Gene Rayburn?

BD Howie Mandel, on “Deal or No Deal,” is the only host in this category, now. The Gene Rayburn style of host, of any show, is mostly gone. Today, television shows are more procedure than content; “CSI” provides the metaphor as well as the fact.

Grahm Junior College

GS Why did you choose to go to Grahm Jr. College, in Boston?

BD It was the best radio and television schools, anywhere, at the time. Today, it doesn’t exist. I likely didn’t have the grades to get into Boston University and Emerson College, which was also in Boston, seemed more focused on Rhetoric and theory, I guess.

I wanted action. I was young. I wanted to produce a hit television show on my first day of classes.

Grahm College had two, not one, A-list colour television studios. What a draw for anyone who wanted to do television. There were a dozen or more radio studios, too.

The calendar Grahm sent made me think the school was all action. This is what I wanted. I didn’t care about anything except creating television: Grahm seemed the place and not all that far from my home in New Rochelle.

GS You were in and out of Grahm quickly.

BD Yes, I left after a year because of “Howdy Doody.” Overtime, I lost touch with Bob Smith, who retired to Florida. One day, I read there was a “Howdy” revival show at the University of Pennsylvania.

Someone at UPenn found Smith playing golf in Florida. The UPenn fellow says, “How’d you like to come to Philadelphia to do a ‘Howdy Doody’ night?” Smith thought the caller was nuts.

The UPenn fellow asks, “Do you have a kinescope of the show?”

Smith says, “I have a kinescope.”

The UPenn fellow asks, “Do you still have the ‘Buffalo Bob’ costume and does it fit?”

Smith says, “Yes, to both questions.”

The UPenn fellow says, “We can do a ‘Howdy’ night, if you’re willing. It’ll be a huge success, for sure.”

Smith and the UPenn fellow work out a deal. Smith flies into Philadelphia, with much apprehension. What college student knows or cares at all about “Howdy Doody”?

Smith, by nature and nurture, was a musician. He played fifteen or twenty instruments, but mostly the piano. His life was music; if you asked Smith what he did for a living, he’s answer, “I’m a musician.” I guess he figures, if the “Howdy” angle didn’t work, he’d make music for two hours.

At UPenn, the show books into a small theatre, holding 1500 people, but 2500 show up. UPenn pipes the show into the foyer and the rest of the theatre building. “Howdy Doody Night” is a huge success and a small industry emerges.

Back in Boston, I read about this show and want to work with "Howdy"; it’s the chance of my lifetime. I think, I must get in on this, not to make money, but because I’m a huge “Howdy Doody” fan. My obstacle was how I could find a place in that show.

Maybe a month later, I read, in the “Phoenix,” a weekly newspaper, in Boston, that there’s a “Howdy Night” coming to the New England Life Hall. I call Vic Smith, brother of Bob, in New Rochelle. “Can you get me together with Bob,” I ask.

A day or two later, Bob calls and says, “We gotta get together. I haven’t seen you in too long. We had dinner before his show at the Life Hall.

There I was, sitting across the table from Bob Smith. He’s wearing a regular sport coat and glasses. He never wore the glasses during a show.

I knew “Buffalo Bob,” the character, well. I knew Bob Smith, but not as well. Now, in 1970, I was getting to know Bob Smith much better.

The show, at the Life Hall, was excellent. The emcee introduced the tenth anniversary “Howdy Doody” show, which plays on a huge screen. “Mr. Bluster” and “Dilly Dally,” major characters from the television show, were ten times bigger than life, on that screen. As some say, “it was to die for.” What a thrill.

The audience ate it up, every crump, every morsel. Keep in mind, in 1970, “Howdy” had been off the air for a decade. That’s half the life time or more of most women and men in the audience.

At the end of the anniversary show, Smith walks out, as “Buffalo Bob.” The audience erupts in joy. Not knowing who appeared, you’d guess a major rock music star, of the day, not a middle-aged musician, with a puppet.

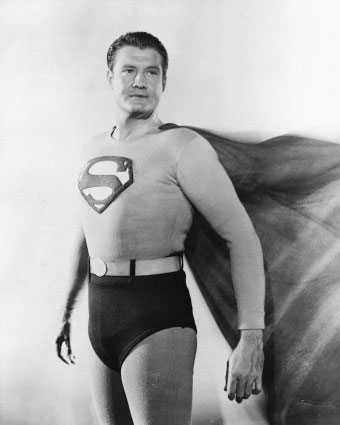

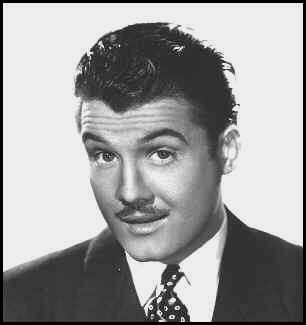

Not two hours before, I had dinner with a bespectacled, sport-coat wearing Bob Smith. Now, here he was as “Buffalo Bob.” It was like Clark Kent and Superman; the transformation astounded.

Smith did ninety minutes. He played music and sang. He took a great many questions.

I knew I had to find a way into this show, what a thrill. Next day, I called Vic Smith. I said, “We gotta figure out how I’m involved in this show.”

To make a long, interesting story short, Bob hired me as road manager for the show. I left Grahm. I emceed all the “Howdy” shows. We worked the road for five years, which seemed as a moment.

Becoming a Television Producer

GS What an experience, an undreamt-of boyhood fantasy comes true. We should all be so fortunate. Yet, there’s much more from your brief time at Grahm Junior College.

BD First day at Grahm, terrible news struck me. The school conveniently forgot to mention a most important fact. First year students had to keep their hands off all the equipment on campus.

I chose Grahm because I thought I could work the equipment, on day one. I guess I missed the part, in their brochure, that said hands-off for first year students. This, of course, defeated my purpose.

GS Your cunning found the loophole.

BD Yes, Grahm owned a television station, WCVB-TV. It broadcast inside the school, from a studio in Kenmore Square. Still, it was television and first-year students could work equipment.

I created a show called, “Grahm Spotlight.” The idea was a “Tonight Show,” on WCVB-TV, for the Grahm student audience. I hosted the show. I produced it. I booked the guests. I sat behind a desk. There were two chairs for guests. It was my version of a television talk show, in 1970.

GS Not a lot has changed.

BD Right, eventually word got around and celebrities would come by, if they were working Boston. Joan Rivers did “Grahm Spotlight.” So, too, did Muhammad Ali.

Two or three weeks into the run of the show, someone knocks on my dorm room door. When I open the door, this fellow is standing there, telling me he’s seen the show and wants to appear on it. Immediately, I think I’m a major television producer; someone wants to be on my show.

I tell the fellow sure and we should talk about it. He says he idolizes “Howdy Doody.” I tell him to come into my dorm room and take the best seat, which, of course, is the floor.

He tells me he likes everything from the 1950s, especially Elvis. He did an impersonation of Elvis. From that moment, we developed a strong, lifelong friendship.

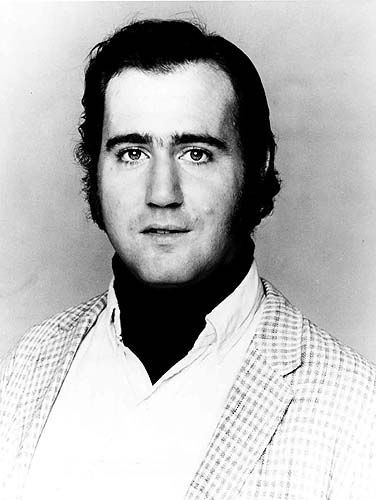

BD Yes, I eventually learned his name. He claimed to be a “song and dance man,” not a comedian. Kaufman was a regular on “Grahm Spotlight.”

On the show, Kaufman (above) did a spoof called, “Uncle Andy's Funhouse,” which was kid oriented. It seems he was on “Grahm Spotlight” every week, but it was likely every two or three weeks. Those memories are so vivid.

First time on the show, Kaufman talked about meeting Elvis. Then he did an impersonation of Elvis. It was a terrible impersonation because he worked the pop culture essence, not only the image, of Elvis.

Kaufman also did a recurring character, on “Grahm Spotlight,” called “Foreign Man.” Eventually, “Foreign Man” became “Latka,” on the sitcom, “Taxi.” I think he might have done an early “Tony Clifton,” too.

When Kaufman appeared on the first “Saturday Night Live” (SNL), he mouthed the words to part of the chorus of the theme from the “Mighty Mouse” cartoon. He used my record for that bit. It was an album called, “Television Theme Songs.”

GS Kaufman, the performer, dressed as a 1950s era television host.

BD Yes, he usually wore a check jacket, beige pants and a turtleneck sweater.

GS Can you talk a little bit about Andy Kaufman.

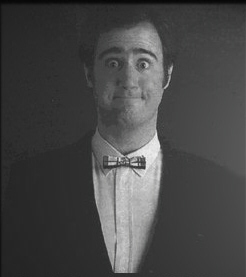

BD Sure, Kaufman wanted to get a reaction, nothing else. He didn't care as long as he got a reaction. He was equally happy when audiences booed him or laughed; it was a reaction.

He and I talked much about reaction, regardless of form. That's what he cared about, a reaction. I used to go with him to “Catch a Rising Star” or the” Improv,” comedy clubs in Los Angeles. This was way before anybody knew of him or his vast talent. He used to bring a sleeping bag on the stage; if his act went bad or not the way he hoped, he'd open the bag and go to sleep; that was it.

Usually, he was the last person on anyway. It didn't matter, if he went to sleep. All was fine.

When the viewers, of SNL, voted him off the show, that was a reaction and he was happy. Kaufman sold out Carnegie Hall, one night. At the end of the show, he asked the 2,800 women and men in the audience to join him for milk and cookies; most did and that was a reaction.

That was the honest Andy Kaufman. He meticulously planned everything he did. He thought out everything he did. Everything he did was funny, but done for a reaction, mostly.

Kaufman was not crazy. Everybody thought he was crazy. When he did “Tony Clifton,” people said that convinced them he was insane.

Kaufman as "Tony Clifton," "Latka Gravas" on� "Taxi" and Elvis Presley

GS The “Tony Clifton” character was innovative and rebelious.

BD Yes, but thoroughly thought out. Kaufman knew what he was doing. He just didn't care if he pissed off anybody. He cared only if he got a reaction.

When I was at QUBE, he was doing “Taxi.” I called him because I needed his help. QUBE existed in the middle of Columbus, Ohio, with little national attention and few celebrities passing through or willing to appear on one show or another.

I could use a name. I said help. Kaufman says, “I’ll come to Columbus, if I can bring Bob Zemuda.” Zemuda was his writer.

Kaufman and Zemuda came to do “Columbus Goes Bananas.” On air, they get into a huge fight, a huge brawl. It was hilarious, every move and moment planned.

After the show, we’re in my car, supposedly heading to the hotel where Kaufman and Zemuda were staying. As we drive along, I happen to mention there’s another show, a live show, airing at that moment. It was a “Today Show,” of a sort, targeted locally and called, “Columbus Live.”

I look in the rear-view mirror, of the car. I see Kaufman has a look on his face I won’t forget. He says, “Can we go see ‘Columbus Live’?” I say sure.

Kaufman says, “I think it’s time for ‘Tony Clifton’.” In the rear-view mirror, I can see him change and transform into “Tony Clifton.” The Clifton character is the most obnoxious lounge singer you can imagine.

At “Columbus Live,” Kaufman as Clifton walks right on to the show. It was horrendous, he insulted everyone and I almost lost my job. Yet, the show never got more reaction, in its run, than for “Tony Clifton.”

Kaufman didn’t care. He got a reaction. Reaction, good or bad, was all he wanted.

GS No one ever understood American pop culture as well as did Kaufman.

BD That was his secret. It all came from the past, too. He was a child of the 1950s.

After years of trying, Kaufman finally got a show on ABC-TV. It was a special, satirically called, “The Andy Kaufman Show.” When ABC negotiated, with Kaufman, for the show, he scared the executives; they wondered about what he might do.

Three weeks before his special was to air, Kaufman calls me. “I got the show,” he says. “I need a big favour.”

“Tell me what you need,” I say, “and you’ll have it.”

Kaufman says, “The network says I can have anyone I want, on the show. We have the money. I want ‘Howdy Doody’ as my special guest.”

I say, “I’ll call Bob, right now.”

Kaufman says, “No, I don’t want Bob Smith. I only want ‘Howdy’.”

“Howdy” rarely appeared without Bob Smith. When I talked, with Smith, I had to tiptoe around the issue. In the end, Smith did it for me.

Smith flew to California. He recorded the voice and “Howdy” appeared alone, with Kaufman. It was a touching moment.

It was the first time Kaufman saw “Howdy,” other than on television. “Howdy” was so important to Kaufman and he wanted the moment to be honest. There was no rehearsal, no green room chitchat, only the genuine first time meeting of Kaufman and a hero from his childhood.

Talk Television

GS How did you find your way into television talk?

BD In the early 1970s, I was on the road with “Buffalo Bob” and “Howdy.” During a break from touring, I became involved with the Muscular Distrophy (MD) Telethon, in Boston, Massachusetts. Bob Kennedy hosted the Telethon.

Kennedy had worked at WBZ-AM, in Boston, but left for WLS-TV, ABC 7, in Chicago; that was in the middle 1960s. Still, he returned to Boston, each year, to do the MD Telethon. About 1974, I think, I met him.

We, Kennedy and I, talked for a while. He said he wanted to hire me for his AM television show, “Kennedy and Company,” at WLS-TV. He had the WLS-TV programme director fly to Boston to talk, with me, and, as it turned out, offer me a job.

That was it. I was in television. I was a producer on “Kennedy and Company.”

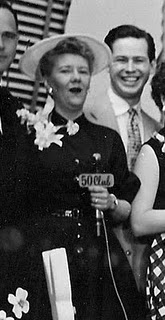

GS You mentioned Ruth Lyons (above), when we first spoke; she was a major force in developing television talk shows.

BD When Avco was Avco, before it became Metromedia, then Multimedia, Ruth Lyons was the queen of media talk in Ohio. She hosted a regionally syndicated television show. Her audience was as loyal and active as are those who watch Oprah. If Lyons said, “Go buy this product,” her viewers did.

I was close with Walter Bartlett, CEO of Multimedia. When I started working for the company and wanted to start new talk shows, he told me about Ruth Lyons. At the time, she was Multimedia.

Lyons was the top on-air asset of the company. She was the company. The company had no show or personality bigger than was Lyons.

She did a Mike Douglas style show, with a band and five singers. Ruth Lyons (below) did all the commercials, live. She was her show. Lyons was what Multimedia took to the bank.

“One day,” says Bartlett, “Lyons tells me she needs a new piano. A piano was expensive and spending that much money, on the word of her bandleader, was iffy. I tried to say no, gently.

“Next day,” says Bartlett, “I’m pulling into the parking lot and there’s a huge truck, from a local piano story, unloading near the studio door. Lyons thought the heck with [Bartlett] and bought the piano. She had that much authority around here. There was nothing I could say or do.”

GS Lyons attracted many huge stars, when they were in the Midwest.

BD Bob Hope used to drop by her show, at least once a month. She created an important tour stop for many stars, one I couldn’t match at QUBE, in Columbus. Ruth Lyons owned television in the Midwestern USA, for a many, many years.

Lyons did her show from WLWT-TV, in Cincinnati. When she retired, in 1967, Bob Braun took over. That’s how I got to Multimedia: I worked on the Braun show.

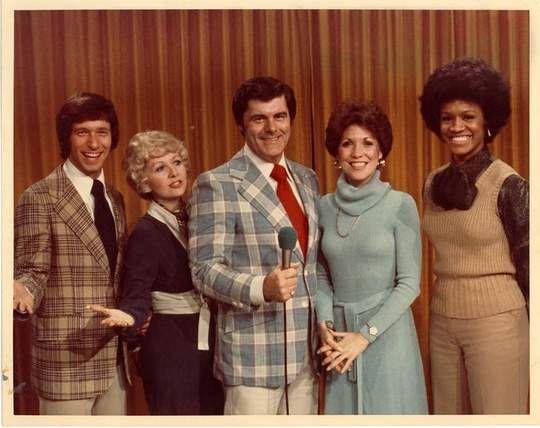

Bob Braun, first day on-air at WLW-AM, 1957; noon show, on WLWT-TV, about 1969; AM Drive DJ, on WSAI-AM, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1999, holding photograph of him interviewing comedian, Red Skelton, on WLTW-TV.

GS Bob Braun is not a name well know beyond the American Midwest.

BD WLW-AM hired Braun, a singer, after he won on "Arthur Talent Scouts." He was a good fit to succeed Ruth Lyons. His show, at noon, aired until 1984.

His show was live for 90 minutes, five days a week. That was much work: 7.5 hours on-air took ten times that long or longer to put together. I was executive producer of the Braun show.

One day the telephone light started flashing, just as Braun went to air. Bob Hope was downstairs, in the lobbying. He wanted to come on the show.

I was new to executive producing a daily, live show, at the time. The sudden appearance of Bob Hope flustered me; no one booked him for today, I thought. What do I do?

Shows how green I was. Bob Hope is downstairs and wants to drop in on the show, now. A top entertainer wants to drop in on Braun and I had to think about it.

After that show, I came to know Bob Hope, well. He was another wonderful megastar. He did “Sally,” any time he was working the St. Louis area.

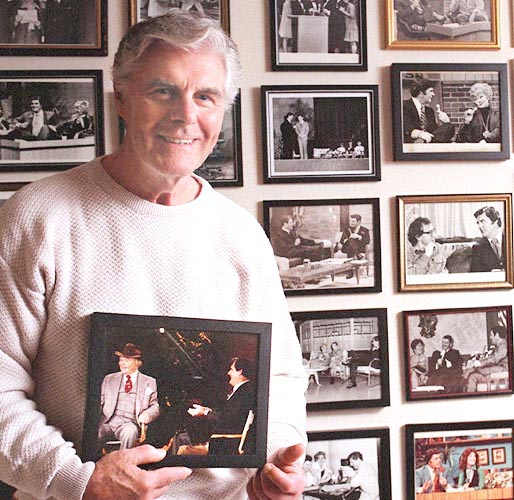

GS You worked the “Mike Douglas Show,” (above) after leaving WLS-TV, in Chicago. What was it like, working a top daytime television talk show?

BD Just what you think. I moved from WLS-TV, in Chicago, to Philadelphia, to work on the “Douglas Show.” It was a giant leap for this man.

Mike Douglas (above) was a wonderful man, a great man, a charming man. He was not a control freak, as are many stars. He had great confidence and did his job, well.

Douglas was the classic example of making it look so easy that viewers thought he was not bright. He was, in fact, bright and wonderful. He especially liked me, I think, because I was the youngest on set; we stayed friendly right to the end of his life.

Douglas was a former big-band singer. Most talk shows begin with the host, such as David Letterman, doing a brief monologue. Douglas opened with a song and moved on to light chat, with guests, and sing more songs.

Early in its run, the Douglas show was live, five days a week, but that ended, in 1965. Zsa Zsa Gabor is an actor renowned for her well knowness and talk show appearances. One day she called the comedian, Morey Amsterdam, “a son of a bitch,” on the live show.

That was the end of the live “Mike Douglas Show.” From that moment, the show ran on a one-day delay. There was no more going live to air.

Mike Douglas retired, in 1982. He did 6000 shows over 21 years. The time for easy-going talk shows ended. Maybe Douglas saw the future.

GS To keep your movement straight, you went from WLS-TV to the “Douglas Show” and then to the “Bob Braun Show.”

BD Yes.

GS The “Sally Jessy Raphael Show” (above) come about while you were producing Braun.

BD Yes, I was doing Bob, which was local, in Cincinnati, with some viewership across the Midwest. I realized if a bus hit Phil Donahue, the doors of Multimedia would close. Braun made money, locally, but Donahue, in national syndication, paid the bills for Multimedia as had Ruth Lyons, in the early days of television talk. Multimedia didn’t realize it, but it needed a backup show.

I wanted to find my way, too. I wanted to find my Mike Douglas, if you will. I wanted to develop a talk show on my own, not take over what someone else started.

GS Some job security, too, I suspect.

BD No question about that, either. I talked with Walter Bartlett, who ran Multimedia. If I found the right person, could we start another show? He said, "Sure you can do it. If you find the person, we'll go ahead.” We signed a small development deal.

One day, while I was still with Braun, a booker calls. “Would you like to have Sally Jessy Raphael on your show,” she asks. At first, I thought it was three people. I had no idea.

The booker explains Raphael is working Talknet, on NBC radio. I agreed to have her guest on Braun. In those days, if anyone had a pulse, we booked her or him for Braun; our standards, at the time, were especially high.

When Raphael appeared on Braun, it was obvious she was the woman to do the new show I imagined. She was a radio star, with no success on television. Raphael wanted to do television, but was unable to find the right show.

My instinct about talent is usually good and I had an idea. Bob Braun was going on vacation for a week. Usually this meant a local game show host replaced him.

My idea was to have Raphael fill in for Braun on five shows. That’s five pilots for her show. A pilot show, without spending a nickel, it was great.

That’s what I did. Raphael came to Cincinnati to do the shows. I made sure the shows provided much fodder for her demo reel, which we would shop around.

Bartlett watched the reel and loved it. Then he told me that about two years before, someone mentioned Raphael to him. Phil Donahue and his wife, the actor, Marlo Thomas, were vacationing. They heard Raphael on radio and concluded she might work, well, for Multimedia Television. Bartlett circulated a memo about Raphael, but nothing came of it.

Coincidentally, I found Raphael. In a sense, Multimedia was presold. The “Sally Jessy Raphael Show” began airing, from St. Louis, on 17 October 1983. Actor Kevin Kline, who is from St. Louis, was the first guest.

GS Mike Douglas helped Raphael.

BD When I started “Sally Jessy Raphael,” in 1983, we were in St. Louis. I needed a guest. I needed some press.

Douglas finished the Westinghouse show, replaced by John Davidson who failed. Douglas was living in Florida, not doing interviews, but I called him.

I asked him to appear on “Sally.” I said, "Mike, remember when you started the show in Cleveland?"

Douglas said "Oh, of course I do.

I said, "Well, your Cleveland is now my St. Louis. I need help. Is there any way I can get you to do a show, with us."

He did. It was a big booking. We got Mike Douglas.

On Raphael, Douglas talked about everything. He did me that favour. Mike Douglas was a great man.

In early 1984, Raphael added a second television station in Grand Rapids, Michigan: our syndication began. Multimedia allowed the show to grow. Then along came “Oprah.”

GS Elvis left the building and Oprah-zilla arrived.

BD Growth of the Raphael show slowed, after Oprah replaced Donahue in the daytime slot. Being a mature producer, I refused to watch “Oprah.” Then I had to watch “Oprah,” to save Raphael.

In the early days, every guest on “Oprah” cried. I thought if you want crying, I’ll give you crying. The Raphael show got to a point where she’d say, “How are ya,” and the audience started to cry.

Then Raphael started to grow, again. The show aired in new markets across the USA. Still, Raphael seldom came up in articles or conversations about daytime television talk. “Oprah,” “Geraldo” and “Donahue,” now with NBC, got the coverage, Raphael didn’t.

GS Much as was Montel Williams, lost in a crowd.

BD Yes, but in time, the Raphael show found its voice and garnered much media attention. It won two Emmys. The red-rimmed eyeglasses, which Raphael didn’t like, became her trademark and brought her much attention.

GS I notice that David Letterman wears red-rimmed glasses, today. Homage, I wonder.

BD May be homage. Toward the end, Raphael was doing shows that weren’t her style. She decided, I think, to let Maury Povich have that audience. She retired, after nineteen years in syndication.

GS Did you stay with Raphael for the full run of the show?

BD No, I left after 15 or 16 years. I have the first pair of her red glasses. I keep everything I can; I’m a pack rat.

GS What's your take on how the “Jerry Springer Show” (above) came about?

BD Well, when I produced the Bob Braun show, pre-Raphael, Springer, the one-time mayor of Cincinnati, did news commentary for us. About this time, he took control of the WLWT-TV evening news show, when its ratings hit bottom. In two years, the WLWT-TV evening news show was number one, in the Cincinnati market.

Springer attracted much attention. Instinctively, I knew Springer was an ideal talk show host. As well, Multimedia was making money from his on-air work: it knew him as successful.

Springer and I connected. I loved him and his work. I wanted to do a show with Springer, but, by that time, the Raphael show was underway.

I figured, let Raphael get going, find its legs, then come back to Springer. Having one hit show is good, but maybe lucky. Two hits shows and networks believe you know what you’re doing.

Once Raphael was stable and growing, I went back to Walter Bartlett, at Multimedia. I wanted to try another show, with Springer. Multimedia owned WLWT-TV, Springer was a bottomless well of profit for the station and the company.

I thought Multimedia wouldn’t release Springer from WLWT-TV. He was important to the company, on a local level, for reasons of profit and prestige. For Multimedia, in Cincinnati, Springer was golden.

Bartlett, to his credit, saw the larger picture. If Springer could repeat Raphael, Multimedia would make much more money than it might give up at WLWT-TV. Multimedia could do better, financially, if it successfully syndicated Springer than it could, with him, locally.

GS There seems some issue about prestige rewards.

BD Maybe, but let’s come back to that in a moment. This is how the Springer show came about. We filmed, first, in Cincinnati. Then the NBC owned stations signed up for Springer, as a group, but only if we would film the show at WMAQ-TV, the NBC station in Chicago.

GS Wasn’t Springer originally more news and public affairs.

BD Yes, Springer was more like Donahue, in the beginning. Springer was in the audience, rephrasing audience questions for the guest. He mediated and moderated on that version of the “Jerry Springer Show.”

That version flopped. An appearance, on the show, by the Rev. Jesse Jackson, was the lowest rated episode. Everyone wanted crying and outrageous guests in daytime.

One day, there was a spontaneous fight at a taping; we aired the m�l�e. Springer began to take off when we innocently booked a woman from California. She lived in her car, with her two daughters, and something, I can’t recall exactly what, lead to another fight on that show.

We recognized what it did for the ratings. I had learned to respect a reaction, as an end in itself, from Andy Kaufman. The reaction, to the wilder Springer shows, was great: the wilder the show, the better the reaction.

We decided to make the most of the yelling, screaming and fighting. We developed a younger live audience and exploited, in a sense, some personal problems. Springer, instinctively, hit on a way to fit into the new approach.

GS Can you describe the new approach Springer developed.

BD Springer always remains at a distance from the antics, but is never detached. He doesn’t get in fights or yelling matches. He remains calm, without an air of superiority and with much authority. You only have to watch one episode, of Springer, to understand what I’m saying.

At the end of the show, Springer makes sense of the mayhem. We’d have a transvestite, wearing chocolate ice cream panties, booked with two large women who bounced their former 120-pound boyfriend around the stage. At the end of the show, Springer sits on his stool and makes sense of the goings-on, which is good, but disarming.

GS Maybe this arises from his stoic British origins. Maybe it stems from the fact he’s a lawyer.

BD Where it comes from doesn’t matter, I guess, that it works, well, is what counts. I hired Richard Dominick, a sometimes television writer and somestime comedian, to revamp and, eventually, produce the Springer show. He wanted to leave the show almost from the day he arrived. About the same time, I hired an Executive Producer, a woman, who did not get on with Dominick.

Dominick had some good reasons to leave the Springer show. I promised to move him up, at some point. I was good to my word.

After a time, Multimedia moved me to Senior Vice-president of Programming. Terry Weible Murphy left Springer to do the “Gordon Elliot Show.” DominickD became Producer of the Springer show; that was probably 1992.

Dominick did a great job. There was much negotiation, with Multimedia, about violence, on the Springer show. He handled well.

Multimedia

GS Why do you think Multimedia had so much success with talk television?

BD Well, Crosley Broadcasting, which started in the early days of radio networks, formed the radio and television side of Avco. Then Avco became Multimedia. The company decided to go with Phil Donahue and he took off.

When Multimedia hired a producer, for a talk show, it asked only the show be a success. Not once, on Raphael or Springer, did Dick Thrall, the executive from Multimedia, who oversaw these shows, ever say to me do this or do that. The company hired a producer, in my case, and gave me all the autonomy you could imagine; management never interfered.

It’s different, today, management instructs talent. Do this, don’t do that. This ruins shows, with too much formula.

GS It’s also easy, today, to pass the blame to executive producers or talent, when a show flops, even though management made the content decisions.

BD Yes, but at Multimedia, when I worked it, producers used their judgment. If a producer succeeded at Multimedia, she or he had his or her contract renewed. Didn’t succeed, you were looking for new work.

When management comes from the creative side of the business, talent gets almost total freedom. When management comes from sales or another industry, creative freedom is the first casualty. Successful television is not the result of bureaucratic controls.

Television talk is what the Multimedia did and does, locally and in national and international syndication. Locally, Ruth Lyons made much money, as did Paul Dickson and Bob Braun. Donahue was successful; then came Raphael and Springer.

When a company does something right, it must keep working what it knows. That’s what Multimedia did. Raphael and Springer, for whatever critics claim, continued a tradition that went back to Crosley and the first days of radio.

I know it seems too simple, but that’s the truth and the secret. Find what you can do well. Stick to what you know, branch out when you take a hit.

GS When did you leave Multimedia?

BD The middle 1990s, I think.

GS There's some speculation you left Springer because of clashes, with other producers, over the content of the show.

BD Not true, in the least, and that's the fact. My leaving Multimedia had nothing to do with any other producer, as some suggest. It was time for me to move, to create other television programmes; it's that simple.

GS The Springer show is rude and crude, the most philistine of all daytime television talk shows, despite Povich. The rudeness is not you, in any way. How that influence your decision to leave Multimedia?

BD The answer is some, maybe, but probably not much. Many Americans don’t believe people, such as the guests on Springer, exist. These women and men live. What you see, on Springer, is how they live. Their lives are sad but true. Some guests may exaggerate or invent their circumstances, but most don’t.

The horrible circumstances you see on Springer are normal for the guests. These women and men live through serial entanglements, more horrible than most of us can imagine. What you see on Springer is the honest lives of these women and men.

GS Sometimes I watch Springer and think many of his guests, a few recently out of prison, commit crimes to go to jail to save their sanity.

BD Yes, America isn’t a middle-class world, of education and degrees of refinement, which many want to believe. The lives seen on Springer are about survival, easing the pain, endlessly searching for balance or harmony, in a world of infinite chaos. The circumstances Springer presents are bizarre, more bizarre than most of us can understand, but true to life for the guests.

If you live in normally bad circumstances, you go on Oprah. If your circumstances are terrible, irresolvable and so horrible that most viewers can’t imagine, you go on Springer. When women and men appear on Springer, they’re as much asking for help as saying, “See, this is how we live.”

GS Springer became a cartoon, I think. Maybe what confounds occasional viewers of Springer is that he seems more dignified, with more integrity, than the content of his show. He stands, at stage right, arms akimbo, following the action.

BD Springer would be the first to confirm what you said. I would like to think that I am, too. The show has nothing to do with us, but with the guests.

Yes, the lives of the guests on the Springer show stink. We can’t ignore a large part of the population; they have a right to free expression, too. Seeing the depths of their despair may help others to avoid that lifestyle or, best of all, make the viewers want to help the guests.

GS Point taken, but how do you defend “Jerry Beads,” for example, given to women who expose themselves on the show.

BD Well, listen, we never went out of our way to say, to the guests, “do this or don’t do that.” The producers tolerated too much unfettered going-one-better competition; I think that’s what happened. The guests on the show today want to top the guests on the show yesterday.

The more craziness tolerated, the crazier the guests became and the bizarre content grew more acceptable for the show, but maybe not for mainstream America. I don’t think viewers take the more outrageous guests seriously; the show became more of a circus.

GS Maybe, the more outrageous the Springer show guests, the less seriously viewers take it and the less harm the show did or does.

BD That’s true. It’s the cartoon image of the Springer show. Cartoonish images or antics don’t influence a normal child or adult. Laughing at the antics is different from copying what the guests are doing.

Sadly, in the end, few viewers sense any sympathy for the guests. Mostly, viewers laugh at the guests. Springer is diversion, like violent movies, with hardly any effect on how viewers act or think.

GS Yes, do it for the money and momentary celebrity.

BD It’s the whole “15 minutes of fame.” Guests want to play along, to have fun, as does the audience of a revival ministry, in a tent, in the Midwest, but you can’t tell them what to do and expect it to happen. Guests on Springer are not actors; they don’t take direction, well.

GS They learn, well, from watching the show, how to be what you want them to be.

BD You can look at it from many standpoints. Sure, some guests want their 15 minutes of fame. Some guests are heartfelt. Most of the guests are who they are; they raised the volume, often, but as themselves.

GS I’m glad to hear you say it.

Daytime Television

GS What’s your take on daytime television talk, 2010?

BD “The View” is the only show worth watching, in daytime. The chemistry, among the co-hosts, is exceptional. Whoopi Goldberg was an intelligent addition to the show. She’s not afraid to speak her mind, what she says, she says well, and she speaks for many, if not most, of her audience.

Goldberg found new audiences, when she joined “The View.” She found a new or renewed audience for herself. She brought a new audience to “The View.”

GS What’s the future for daytime television talk?

BD I’m not sure. Many suggest the Internet is getting in the way. I don’t buy it.

The web remains a short form, snippets of this and that, brief videos, even briefer blog comments, with no change in sight. Daytime television talk is a much longer form, offering a unique product and much choice. The web and highly pruned text messages can’t convey the larger nature of most issues.

If the talk is interesting and the host is good, daytime television talk attracts a large audience. Shows will come and go, at least for now. Yet, the format remains mostly the same.

Marie Osmond is sure to return, maybe in 2011 or 2012. She belongs in daytime. I was ready to produce a daytime talk show, with Osmond, for September 2009, but business matters got in the way; we postponed.

Ellen DeGeneres will continue, long after Oprah leaves. Howie Mandel is another strong possibility. There are many others, too, most not yet discovered.

If a host can bond, with the audience, and it’s not an easy task, the payoff is loyalty. All television talk, daytime or night, rides on personality and the resulting loyalty. The key, I believe, is to make the show simple and mostly predictable; listeners then find a comfort zone in your show.

GS Is there an alternative way to do daytime television talk, successfully.

BD We can’t reinvent the wheel. In the 1970s, Dr. Joyce Brothers did what Dr. Phil does today. David Letterman proudly admits “Late Night” owes its success to the “Tonight Show,” when Steve Allen was host, in the 1950s, and Johnny Carson, too.

“The View” is a new way, of sorts, to do an existing format, successfully. There are four or five hosts, not one. The show works well.

GS You were close to Paul Winchell, the ventriloquist, an entertainer of huge proportions, from about 1940 to 1975.

BD A wonderful, talented man was Paul Winchell. He was brilliant, a genius and not only as an entertainer. It was my good fortune to know him.

He worked with several puppets, including Knucklehead Smiff. Jerry Mahoney had a network radio show in the 1940s, a competitor for Charlie McCarthy. The career, of Winchell and Mahoney, boomed in the 1950s and 1960s; “Winchell-Mahoney Time,” a television show, was top rated from 1965 to 1968.

GS How did you meet Winchell? I heard he was a loner.

BD Often, I wanted to meet celebrities, such as Paul Winchell, but didn’t have the wherewithal. Producing Raphael opened the door. I’d find a reason to book whomever I wanted to meet on the show.

GS Job benefits come in many forms.

BD Winchell wasn’t only a ventrilo1quist. He invented the artificial heart, US Patent 3097366. I called Winchell, pitching the idea he appear, on Raphael, as the man who invented the artificial heart.

At first, he wouldn’t talk with me. I said, “We have a mutual friend.”

Winchell says, “Who’s that?” He didn’t believe me.

“Hank Heimlich,” I said. He developed the Heimlich Manoeuver. He guided Winchell through his invention of the artificial heart.

I say, to Winchell, “If I put Hank on with you, would you do the show?”

We went back and forth. Finally, to shut me up, Winchell says, “Yes, if you can get Hank, I’ll do your show.” I’m sure he didn’t think I could get Heimlich.

I called Heimlich, who lived in Cincinnati and was often a guest on Braun. “You must do me a favour,” I say. I tell Heimlich that Winchell will do the Raphael show, if he joins him.

I call Winchell back, saying, “I talked with Heimlich. He’ll do the show.”

“No he won’t,” says Winchell.

“Okay,” I say, “you call Heimlich.”

A few weeks later, Winchell and Heimlich are on Raphael. That was 1985. That’s when my friendship with Winchell began. It lasted until his death in June 2005.

"Jerry Mahoney," Paul Winchell and "Knucklehead"

GS Why do you think Winchell was difficult?

BD He overcame much, early in his life. Winchell had Polio as a child, one leg shorter than his other leg. He built up his shoe, so you never saw the limp. He stuttered, too. These minor drawbacks plagued him.

More serious, as a child Winchell suffered mental abuse from his mother. Maybe she didn’t think he was a perfect child. Maybe she had her own demons. I don’t know any reason for her relentless abuse of her son, only that it happened and he lived with the scaring.

Winchell was a tortured man. He was unhappy, but brilliant. If he had his way, he would’ve gone to medical school, but he fell into show business.

GS In his day, the 1930s, I guess, show business was a good choice, if you couldn’t go to university and had a smidgen of talent.

BD That’s true. I was lucky enough to be one of the few people Winchell chose to befriend through the last 20 years of his life. He would see almost no one. Often, even his children couldn’t see him.

Winchell didn’t hang around ventriloquists and such. He was an intellect. He wrote two or three books on religion.

His life was difficult, in the beginning, He didn’t fully get over that, if any of us would, and isolation made his adult life easier, I guess. Still, he was fine with me.

GS Winchell took to you.

BD Yes, he did. Winchell gave me all of his stuff. I have 40 or 50 hours of exceptional material. Most of what he and Mahoney did was live. Luckily, kinescopes, of some Winchell performances, existed. I have all that on DVD.

I did a documentary about him, for a place called VentHaven. It’s is a major ventriloquist centre, in Kentucky. Willy Tyler and Jimmy Nelson, J John and others are in the documentary.

Dubrow with "Jerry Mahoney"

GS Can you tell us about Winchell suing Metromedia.